Summary: The current method for identifying drug trafficking SARs in the FinCEN database is like playing a round of The Family Feud with the category: “Name Something Related to Drug Trafficking.”

Drug trafficking is a national money laundering priority, yet drug trafficking does not have a suspicious activity checkbox on the SAR form. This results in inconsistent reporting by financial institutions, data capture shortfalls, cumbersome SAR queries, lack of public access to basic information on drug trafficking SARs, and government agencies relying on incomplete data when assessing drug traffickers’ money laundering methodologies.

Financial & Human Impact of Drug Trafficking

Drug trafficking is the second largest source of illicit proceeds flowing through the US financial system.[1] The 2018 National Money Laundering Risk Assessment estimated $100 billion dollars in drug trafficking proceeds are generated each year in the United States.

The human cost is also staggering with nearly 107,622 Americans dying of drug overdoses in 2021.

Finally, drug trafficking can also pose national security threats to the United States. The Department of Defense reports:

Many of our nation’s adversaries, including nation-states, non-state actors, and violent extremist organizations (VEOs), depend on proceeds generated from drug trafficking and other illicit activities to fund their operations.

Framework to Counter Drug Trafficking and Other Illicit Threats, 2019, Department of Defense

Drug Trafficking & FinCEN Guidance

FinCEN has issued numerous advisories and guidance on drug trafficking including:

- funnel accounts

- bulk currency corridors

- indicators of fentanyl trafficking

- Trade-Based Money Laundering (TBML) used by Drug Trafficking Organizations (DTOs)

- requiring SARs to be filed on marijuana-related businesses utilizing specific key terms[2] in the SAR narrative.[3]

In addition, the GAO found that drug trafficking organizations have adapted cryptocurrency as a tool to procure inputs, conduct sales and laundered funds.

Drug Trafficking & AML National Priorities

Financial institutions do not have a uniform way to explicitly report suspected drug trafficking financial activity on the SAR form. There are over 90 suspicious activity checkboxes ranging from Ponzi Schemes to Elder Abuse to Mass-Marketing. Yet drug trafficking, which generates over $100 billion dollars annually within the US does not warrant a checkbox.

Consider when two of the AML National Priorities collide- Drug Trafficking Organizations and Virtual Currency.[4] The GAO found that SARs referencing virtual currency and drug trafficking increased fivefold from 252 in 2017 to 1,432 in 2020.

Per the GAO report, to calculate the number of drug trafficking involving virtual currency SARs:

FinCEN officials told us they searched narrative SAR data for common payment methodologies associated with drugs, such as trade-based money laundering, and other controlled substance terms such as drug, narcotics, fentanyl, and the names of cartels.

Virtual Currencies: Additional Information Could Improve Federal Agency Efforts to Counter Human and Drug Trafficking, December 2021, GAO

The difficultly in identifying drug trafficking SARs is not a new problem. FinCEN’s 2010 Advisory on Trade-Based Money Laundering reported:

“SAR filings on suspected TBML are increasing; however, it can be difficult to identify these SARs. Filers clearly identified the activity as TBML or BMPE in only 24 percent of the SAR narratives analyzed in conjunction with the advisory. The remaining 76 percent of the SARs potentially associated with TBML required complex queries that included trade and other terms derived from the red flags identified in this Advisory.”

Advisory to Financial Institutions on Filing Suspicious Activity Reports regarding Trade-Based Money Laundering, February 2010, FinCEN

Improving Usefulness to Law Enforcement

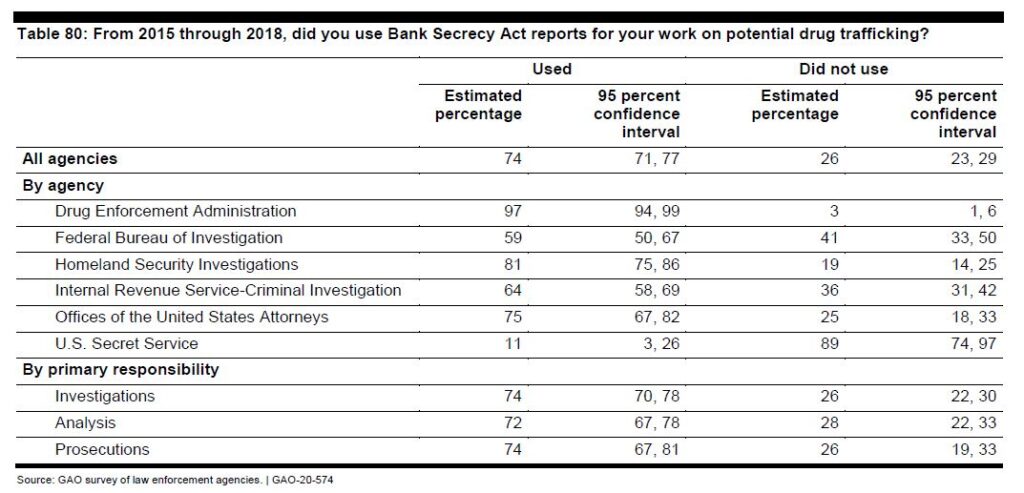

29% of DEA respondents surveyed by the GAO reported “almost always” using Suspicious Activity Reports in their work, yet there is no drug trafficking SAR category. Similarly, 97% of DEA respondents reported using BSA reports on work on drug trafficking.

Clearly, one way to improve the effectiveness of the US’s Anti-Money Laundering regime is to align SAR categories with the both the AML National Priorities and with how BSA data-consumers use the information.

If end-users are searching BSA data regarding drug trafficking cases, there should be a simple way to do this.

SAR checkbox > Narrative Keyword Search

Structured data via a SAR checkbox for drug trafficking will improve AML effectiveness in that the data will become easily searchable. A drug trafficking suspicious activity checkbox will reduce the chance that the IRS-CI, FBI, or DEA will “miss” a relevant SAR. Currently, law enforcement must perform a keyword search and hope that those are the same terms and spellings that financial institutions used in the SAR narrative.

To illustrate the short-comings of keyword-based SAR queries, consider the following from a Treasury audit on SAR data quality:

“of 12,654 SARs file by one institution over the 12 month period evaluated, revealed that the filer spelled the name of the financial institution 85 different ways including several misspellings of the institution’s name.”

The Universal Suspicious Activity Report and Electronic Filing Have Helped Data Quality But Challenges Remain, March 2018, Office of the Inspector General, Department of the Treasury

If one financial institution spells its own name 85 different ways, imagine how many permutations there are in SAR narratives of “controlled substance terms” and “names of cartels” across all SAR filers.

Drug Trafficking SAR Meta-Data

SAR data on a cumulative basis is useful in discovering money laundering and financial crime trends.

For example, DSA’s analysis of how Covid-19 impacted 2020 SAR filings was referenced in testimony before the Senate Caucus on International Narcotics Control:

“A Wall Street Journal report [citing DSA’s analysis] attributed this increase [in Transactions Below the Cash Transaction Report Threshold SARs] to difficulties in smuggling bulk cash across borders and other international COVID travel restrictions. Notably, this type of information is a prime example of the emerging new indicators and intelligence being produced[5] by the Bank Secrecy Act as a result of COVID-19 restrictions.”

Written testimony of Steve Gurdak, Washington/Baltimore High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area- Supervisor, 7/20/21

Lesser known US government agencies also turn to SAR data when researching drug trafficking. For example, the Western Hemisphere Drug Policy Commission is an independent, bipartisan entity with a mission to evaluate US counternarcotics programs in the Americas and then make recommendations to improve them. The Commission’s 2020 report cited my annual analysis of SAR filings. However, neither the Commission nor I was able to answer the simple question of how many SARs involve drug trafficking.

What kind of questions would a Drug Trafficking SAR category answer?

The lack of a drug trafficking SAR category leaves many important questions unanswered.

- How many SARs involve drug trafficking?

- Are drug trafficking SARs rising or fall year over year?

- What financial instruments or products are most often associated with drug trafficking?

- Are the methods used to launder drug trafficking proceeds changing?

- Are there regional differences in drug trafficking money laundering?

- What is the relationship between the drug trafficking SARs subject and the financial institution (ex. customers, employees, unrelated)?

- Do all financial industries (ex. banking, gaming, crypto, etc.) detect drug trafficking effectively?

Conversely, Human Trafficking does have a SAR checkbox. DSA has answered these types of questions about Human Trafficking by analyzing FinCEN SAR Stat data.

It seems inconsistent that these questions can be answered for human trafficking but not for drug trafficking.

Conclusion

Failing to have a drug trafficking SAR category leads to several poor outcomes.

First, financial institutions filing drug trafficking related SARs are left to their own devices in describing the suspicious activity. A uniform method via a drug trafficking checkbox would simplify the process.

Second, law enforcement end-users are likely to miss relevant drug trafficking SARs due to unsuccessful keyword searches.

Finally, important insights into how drug traffickers launder funds are untapped. Drug trafficking related SAR data is unwieldy even to government analysts and locked within FinCEN’s SAR database, inscrutable to the public.

[1] Healthcare fraud generates the largest dollar amount of illicit proceeds. Tax evasion generates the most proceeds that need to be laundered from a licit source.

[2] FinCEN’s webpage listing Suspicious Activity Report Advisory Key Terms does not include the 2014 marijuana key terms. This oversight suggests to me that since FinCEN itself can’t even keep track of the 50+ “key terms”, several of which involve drug trafficking, it’s unlikely that financial institutions are doing any better.

[3] Kemmerling, S. & Jimenez, A. (April 2015) “Who is Filing Suspicious Activity Reports on the Marijuana Industry? New Data May Surprise You.”

[4] There is also no “Virtual Currency” SAR product category, FinCEN also had to keyword search the narrative field to identify virtual currency transactions. FinCEN itself has referred to cryptocurrency with a variety of terms including crypto-currency, convertible virtual currency, CVC, virtual currency, digital currency, virtual assets, AEC, and Bitcoin. Read DSA’s analysis of SARs likely filed by San Francisco-based crypto exchanges here.

[5] To be clear, the Covid-19 SAR analysis was not prepared and disseminated by FinCEN or any other government agency. I produced this analysis using publicly reported SAR data.