DSA submitted a comment letter in response to FinCEN’s Advance Notice of Proposed Rule Making (ANPRM) on AML Program Effectiveness published in the Federal Register on September 17, 2020.

My comments largely focused on two issues: (1) the issuance of Strategic AML Priorities and (2) reporting of information with a high degree of usefulness to government authorities.

Strategic AML Priorities

FinCEN should issue Strategic AML Priorities (“Priorities”) and these Priorities should be incorporated into financial institutions risk assessments.[1] However, the effectiveness of the AML Priorities will be hampered if FinCEN does not also update the Suspicious Activity Report (SAR) form to reflect the Priorities.[2]

The 2020 National Strategy for Combating Terrorist and Other Illicit Financing[3] (‘2020 National Strategy’) was prepared by the Treasury Department in consultation with a variety of other federal agencies to inform how the public and private sectors should prioritize and respond to the challenges posed by illicit finance:

Both the public and private sector should use these finding to prioritize the tools, authorities, and resources. For the public sector stakeholders, this includes law enforcement action, targeted financial measures, the supervision of financial institutions, and the imposition of regulatory obligations. For private sector entities, these findings should also guide deployment of resources to detect and report illicit finance activity and other preventative and risk mitigation measures.

The 2020 National Strategy lists the most significant illicit finance threats facing the United States:

- Money laundering linked to –

-Fraud (healthcare, tax refund, identity theft, bank, e-mail compromise, elder, romance, and securities);

-Cybercrime and cyber-enabled financial crime;

-Drug trafficking;

-Human trafficking and smuggling; and

-Corruption

- Terrorist financing

- WMD proliferation

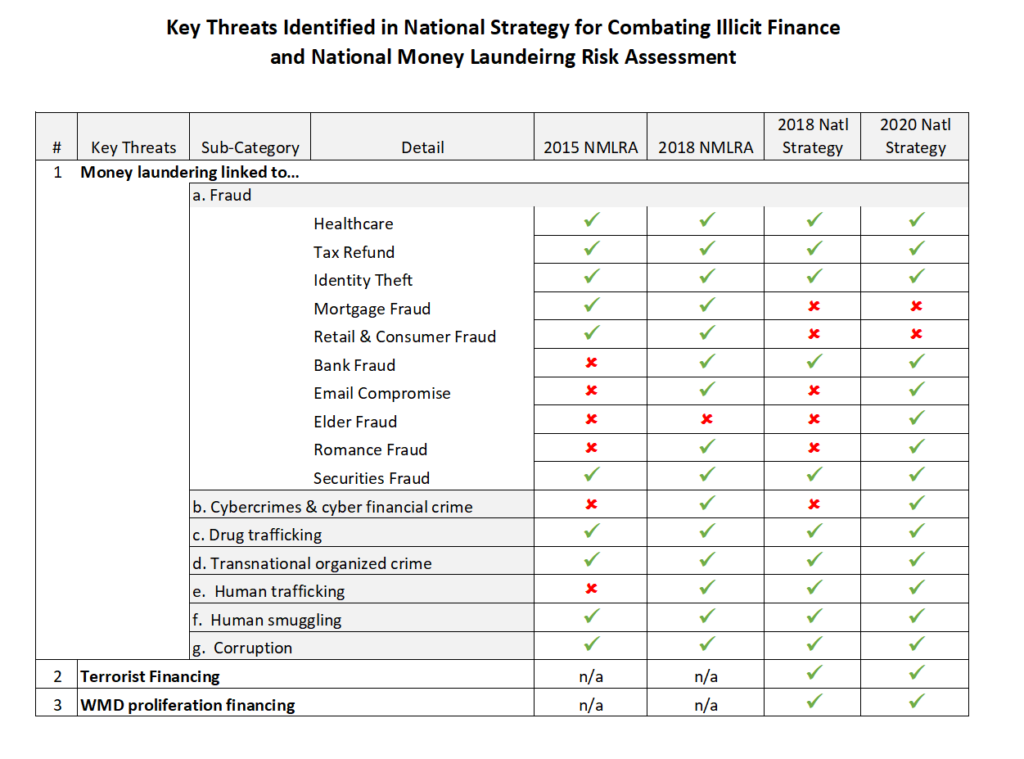

Key Threats Unchanged since 2015

The 2018 National Strategy included a very similar list of the most significant threats. Additionally, the 2015 and the 2018 National Money Laundering Risk Assessments (NMLRA) also included lists with largely the same key threats.[3]

The table below compiles the Key Threats highlighted in the four reports.[4] Notably all the reports include the following Key Threats: Healthcare Fraud, Drug Trafficking, and Transnational Criminal Organizations.

Figure 1

The table shows that for at least five years, Healthcare Fraud was identified by the US government as a Key Threat. These reports all identified Healthcare Fraud as the largest source of illicit funds laundered in the United States with estimates ranging from $110 billion to $230 billion in illicit proceeds each year. Healthcare Fraud generates one out of every three illicit dollars laundered.[5] Drug Trafficking produces the second largest amount of illicit laundered funds in the US.

Arguably, the dollar value of illicit proceeds is not the sole way to gauge threats. Other factors such as vulnerabilities, likelihood, impact, and residual risk should also be weighted. For example, Terror Finance does not involve the same dollar amount as Drug Trafficking, but the government has named it a Key Threat because of its potential impact.

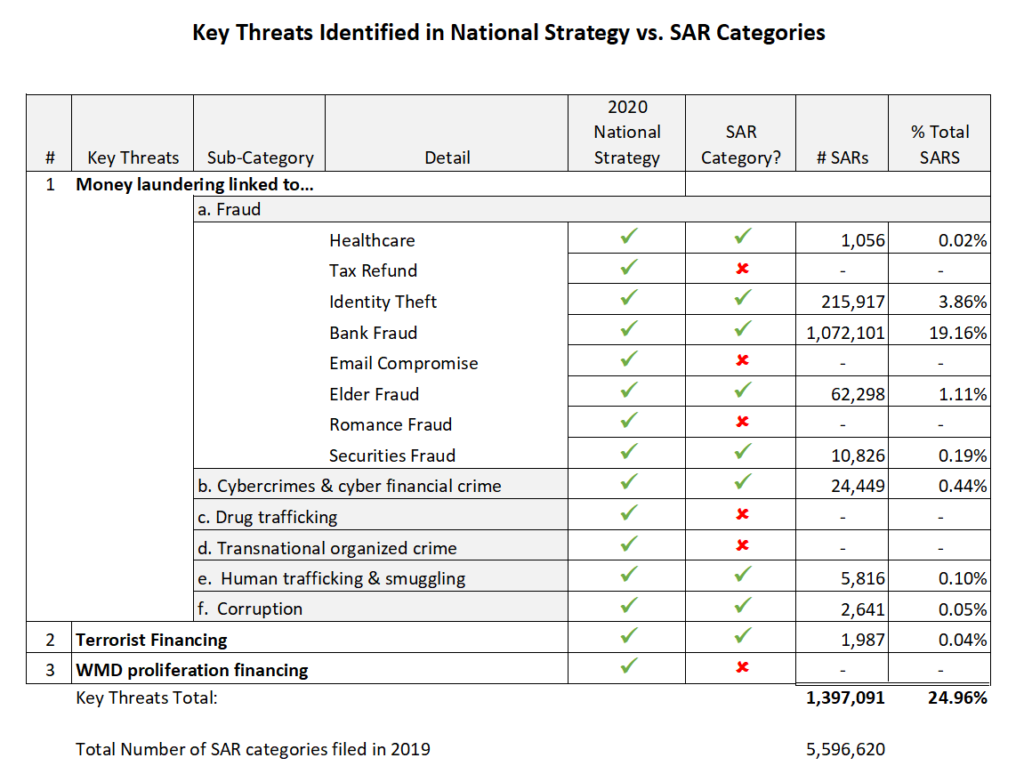

Disconnect between Key Threats and SARs

The table below lists the Key Threats from the 2020 National Strategy along with whether there is a corresponding SAR category and if so, how many SARs were filed in 2019. Some Key Threats such as Bank Fraud include multiple SAR categories (wire fraud, ACH fraud, credit card fraud, etc.) that were totaled in a combined SAR count number.

Figure 2

The SAR form currently has 96 different categories of “suspicious activity” yet several of the Key Threats are not categories on the SAR form. For example, there are no Drug Trafficking, Organized Crime, or WMD Proliferation categories. Additionally, the largest source of illicit proceeds (Healthcare Fraud) is rarely reported. Finally, the largest source of laundered funds, Tax Evasion, is also not a category.

Specific Key Threats

Healthcare Fraud

Healthcare Fraud accounted for 0.02% of SARs filed in 2019[6] yet this fraud generates over 30% of all dirty proceeds in the United States. Healthcare Fraud SARs placed 73rd out of 96 suspicious activity categories in 2019 with only 1,056 SARs filed. By comparison, there were nearly three times as many Human Trafficking SARs, thirteen times as many Mass-Marketing SARs, and sixty-two times as many Elder Financial Exploitation SARs.

The Covid-19 pandemic has underscored the importance of identifying and reporting Healthcare Fraud in the SAR regime.[7] The life-and-death consequences of Healthcare Fraud can manifest in the lack of funds to buy respirators, ineffective drugs being prescribed, and the diversion of funds to Organized Crime groups.

FinCEN should issue Strategic AML Priorities and include Healthcare Fraud. As evidenced by sparse filings of Healthcare Fraud SARs, and despite the enormous financial cost and the loss of life directly attributable to Healthcare Fraud, financial institutions have not made detecting this crime a priority.

There is a dearth of examples of financial institutions facing any type of penalty for failing to detect or report suspicions of Healthcare Fraud. Conversely, numerous banks have been fined to failing to detect crimes such as drug trafficking, corruption, and Ponzi schemes. Therefore, if FinCEN issues AML Priorities but regulators do not issue enforcement actions for failing to file SARs for those Priorities, it is possible that AML program effectiveness will not improve.[8]

Missing AML Priorities

Transnational Organized Crime

Transnational Organized Crime does not have a SAR category. Yet, Transnational Organized Crime is estimated to generate over 40% of all financial crime proceeds.[9] Criminal organizations play a leading role in many of the Key Threats from Human Trafficking to Cybercrime to Romance Scams. Moreover, Organized Crime groups may participate in a variety of crimes simultaneously such as Drug Trafficking, Corruption, and Human Smuggling.[10] Finally, the FBI notes that the vast sums of money involved in Transnational Organized Crime can compromise legitimate economies and have a direct impact on governments through the corruption of public officials.[11]

Consider the leverage that would occur if Organized Crime were added as a SAR category and named a Strategic AML Priority. Whereas any instance of Elder Abuse is one too many, a SAR that identifies a care-giver taking financial advantage of a single dementia patient will not have as wide-spread impact as a SAR that notes an Elder Abuse scheme run out of an overseas call center linked to an Transnational Organized Crime group.

The Anti-Money Laundering regime can improve effectiveness by focusing on the criminal organizations that conduct large scale crimes. FinCEN should both add Organized Crime as a SAR category and provide guidance to financial institutions on indicators of Organized Crime.

SAR Review Teams & Transnational Organized Crime

FinCEN should also study the efficiency and effectiveness of SAR Review Teams geographically linked to US Attorney Office boundaries. As noted above, Transnational Organized Crime generates about 40% of all illicit proceeds. Organized Crime does not respect national boundaries and certainly does not contain their activity to within the jurisdiction of a specific US Attorney. If a SAR Review Team solely focuses on SARs reported within their geographic borders, they may miss large scale organized crime.

Furthermore, I have found that SAR geographic data is extremely inaccurate.[12] My critique of SAR geographic data was confirmed by a Treasury OIG audit of SAR data quality in 2018 that stated “the quality of filer responses in both institution and subject address fields were of particular concern.”[13]

Drug Trafficking

Drug Trafficking does not have a SAR category, yet this crime is most often connected to money laundering in the public’s mind. The 2020 National Strategy estimates $100 billion dollars in drug trafficking proceeds are generated each year in the United States.

The human cost is also staggering with nearly 72,000 Americans dying of drug overdoses in 2019.[14] The 2020 Homeland Security: Homeland Threat Assessment echoes the National Strategy and National Money Laundering Risk Assessment in identifying Drug Trafficking as a major threat.

Additionally, FinCEN has issued numerous Advisories and Guidance regarding drug trafficking ranging from notices about “funnel accounts”[15] to indicators of fentanyl trafficking[16] to requiring SARs to be filed on marijuana-related businesses[17] utilizing specific key terms in the SAR narrative.[18]

Despite the uniformly acknowledged risk, financial institutions do not have a uniform way to explicitly report suspected drug trafficking financial activity on the SAR form.

National Security

FinCEN’s mission statement states:

Promote national security through collection, analysis and dissemination of financial intelligence, and strategic use of financial authorities.

Additionally, 31 USC § 5311 states:

It is the purpose of this subchapter to require certain reports or records where they have a high degree of usefulness in criminal, tax, or regulatory investigations or proceedings, or in the conduct of intelligence or counterintelligence activities, including analysis, to protect against international terrorism.

The 2020 National Strategy includes National Security concerns such as terrorist financing and WMD proliferation financing, the latter of which is not a SAR option. Notably, the 2020 National Strategy did not consult with the Department of Defense, whereas the 2015 version did include DoD input.

The Homeland Threat Assessment reflects additional major threats that are not directly reportable on the SAR form including: WMD financing/proliferation and foreign influence activity (political/military espionage, economic espionage, and amplifying US socio-political division).

Disconnect between the Largest Source of Laundered Funds- Tax Evasion and SARs

The overwhelming majority of laundered funds originate from tax evasion, yet there is no SAR category to directly report this crime.[19] About 68% of all laundered funds are proceeds from tax evasion and when the gross hidden income is included, an estimated 85% of all laundered funds are related to tax evasion.

The IRS last calculated the federal income “tax gap”[20] which is the amount of taxes owed but not paid in a timely or voluntary manner for tax years 2008-2010. The average tax gap was $406 billion per year during that period. The Brookings Institution estimated that the gap would have reached $560 billion by 2018.[21] Put this into perspective, for every $1.00 dollar in drug trafficking proceeds there is $5.60 of tax evasion.

Financial Institutions Look for Money Laundering, Not Limited to Illicit Funds

The FFEIC Manual[22] discusses that banks are not required to determine the underlying crime of a given suspicious activity:

Banks are required to report suspicious activity that may involve money laundering, BSA violations, terrorist financing, and certain other crimes above prescribed dollar thresholds. However, banks are not obligated to investigate or confirm the underlying crime (e.g., terrorist financing, money laundering, tax evasion, identity theft, and various types of fraud). Investigation is the responsibility of law enforcement. When evaluating suspicious activity and completing the SAR, banks should, to the best of their ability, identify the characteristics of the suspicious activity.

Half of the 96 SAR categories of suspicious activity are not linked to any specific crime. About 69% of SAR categories checked in 2019 reflected an “unspecified crime.”[23]

Examples of these general or “unspecified crime” suspicious activity categories include:

- Transaction(s) Below BSA Recordkeeping Thresholds

- Transaction with No Apparent Economic, Business, or Lawful Purpose

- Refused or Avoided Request for Documentation

Someone engaging in tax evasion (from a legal source) would use these same techniques and present the same characteristics of suspicious activity as a criminal laundering money from an illegal source.

Financial institutions detect suspicious activity that is tax evasion at a massive rate. Consider the 480,000 SARs for “Transaction(s) Below BSA Recordkeeping Thresholds” filed in 2019. Hundreds of thousands of the structuring SARs could represent individuals attempting to evade taxes.[24] [25] FinCEN has repeatedly highlighted SARs that were helpful in tax evasion prosecutions.[26]

In conclusion, FinCEN’s suggestion to create National Strategic AML Priorities will help address the disjoint between what financial institutions are asked to report, what they do report, and what the government has repeatedly said are national priorities. But more is needed; including revising the SAR form to include checkboxes for all Strategic Priorities, regulators testing for compliance with the Priorities, and explicitly including Tax Evasion as a SAR category.

Reporting of information with a high degree of usefulness to government authorities

Financial institutions have little insight into what information has a high degree of usefulness to government authorities. Government authorities that use BSA data include federal, state and local law enforcement agencies, counter-terrorism agencies, financial regulators, and the intelligence community.[27]

The only data currently available about how “government agencies” use BSA data is a September 2020 GAO study of six federal law enforcement agencies.[28] Over a quarter of federal law enforcement respondents had not used BSA data at all from 2015 through 2018. The GAO also found that local law enforcement agencies are not using BSA data to assist their investigations.

The irony of the lack of a Tax Evasion SAR category is that the IRS-CI is the most frequent user of BSA data to start new investigations. That said, only 12% of all new IRS-CI investigations start with BSA data[29], yet the agency still ranks ahead of all other federal law enforcement agencies.[30] Similarly, 97% of DEA respondents surveyed reported using BSA reports for drug trafficking cases, yet there is no Drug Trafficking SAR category.[31] Finally, the FBI utilized BSA data in nearly 60 percent of Organized Crime investigations without the benefit of an Organized Crime SAR category.[32]

Clearly, one way to improve the effectiveness of the Anti-Money Laundering Program is to align SARs filings with the both the Strategic Priorities and with how BSA data-consumers use the information. If end-users are searching BSA data regarding tax evasion, organized crime, and drug trafficking cases, there should be a simple way to do this.

Structured data in the form of new SAR checkboxes will improve AML effectiveness in that the data is easily searchable. Unstructured data, such as SAR narrative or open text fields, have no pre-defined organization and makes it much more difficult to collect, process and analyze. Information reported to government authorities is only “useful” inasmuch that it is discoverable in an efficient manner.

New SAR category checkboxes for Tax Evasion, Organized Crime, and Drug Trafficking will reduce the chance that the IRS-CI, FBI, or DEA will “miss” a relevant SAR. Currently, law enforcement must perform a keyword search and hope that those are the same terms (and spellings[33]) that financial institutions used in the SAR narrative.

This may be why the GAO survey found that federal law enforcement view BSA data as a good source for financial data and other information about existing investigations, as opposed to a source for new investigations. When law enforcement has a starting point from an existing case, they can search structured data fields for items such as names, bank account numbers, and IP addresses.

While I agree with the AMLE WG recommendation that:

Stakeholders [should] refocus the national AML regime to place greater emphasis on providing information with a high degree of usefulness to government authorities based on national AML priorities, in order to promote effective outputs over auditable processes and to ensure clearer standards for measuring effectiveness in evaluating AML programs.

It is entirely unclear what government authorities aside from six federal law enforcement agencies find “useful.”[34] Nor can financial institutions influence government agencies to either begin using or increase the use of BSA data. Next, a BSA regulatory oversight agency may measure the effectiveness of a financial institution’s AML program based on information that agency finds “useful” and not consider what another agency finds “useful.” Finally, BSA data on a meta-level is also very “useful” to determine trends, typologies, and emerging threats. It should be clarified that “usefulness” is not limited data in one SAR, but to the overall BSA data eco-system.

[1] Responsive to Question 6: Should FinCEN issue Strategic AML Priorities, and should it do so every two years or at a different interval? Is an explicit requirement that risk assessments consider the Strategic AML Priorities appropriate? [2] Responsive to Question #3: Are the changes to the AML regulations under consideration in this ANPRM an appropriate mechanism to achieve the objectives of increasing the effectiveness of AML programs? If not, what different or additional mechanisms should FinCEN consider? [3] Responsive to Question 6: Should FinCEN should issue Strategic AML Priorities every two years or some other frequency? Two years may be too short a period to determine if BSA filings respond to the Strategic Priorities. Implementing new Priorities could take months at financial institutions. I recommend a four- or five-year period. FinCEN can issue an Advisory in the intervening years if a new item is time sensitive. [4] Figures 1 & 2 originally published in Jimenez, A. (Apr 2020) “The National Strategy on Combatting Illicit Finance vs. Actual SAR Filings.” [5] Tax Evasion is the overall largest source of laundered funds. The funds laundered to evade taxes may have been legally earned. Healthcare Fraud is the largest source of illicit funds, meaning that the funds were generated from illegal activity. See: Jimenez, A. (May 2020) “Tax Evasion: The Largest Source of Laundered Funds”. [6] “2019 SAR Insight: Suspicious Activity Report Annual Analysis” [7] Jimenez, A. (May 2020) “Healthcare Fraud During a Pandemic: Fast Facts for Financial Institutions.” ThomsonReuters. [8] BSA regulatory oversight varies widely by regulator. See Jimenez, A. (Feb 2020) “Which Industry is Really in Peril of being Under-Regulated in AML? An analysis of Federal BSA Regulator Oversight” [9] The UN estimated that the total amount of criminal proceeds generated in 2009, excluding those derived from tax evasion was 3.6% of global GDP. Of that total, transnational organized crime may have accounted to 1.5% of global GDP. [10] Jimenez, A. (Nov 2019) “Migrant Smuggling: What Financial Institutions Need to Know”, Thomson Reuters Legal Executive Institute. [11] https://www.fbi.gov/investigate/organized-crime. Also see Jimenez, A. (Nov 2019) “Analysis of Human Smuggling SARs”. [12] Jimenez, A. (June 2014) “How is Your State Suspicious?” and (Apr 2009) “Are Nebraskans Really the Most Suspicious People in the Nation?” [13] A 2018 Treasury OIG audit of SAR data quality found one or more errors in 33.5% of filings which was an improvement from the 59% error rate found in a similar 2010 audit. For example, batch filers submitted invalid entries for 10.5% Subject-State and 58.76% for Financial Institution-Zip Code data fields. [14] Katz, J. (July 2020). “In Shadow of Pandemic, US Drug Overdose Deaths Resurge to Record”. NYT. [15] “Update on US Currency Restrictions in Mexico: Funnel Accounts and TBML” May 2014. FinCEN. [16] “Advisory to Financial Institutions on Illicit Financial Schemes and Methods Related to the Trafficking of Fentanyl and Other Synthetic Opioids,” August 2019. FinCEN. [17] “BSA Expectations Regarding Marijuana-Related Businesses” February 2014. FinCEN. [18] Kemmerling, S. & Jimenez, A. (April 2015) “Who is Filing Suspicious Activity Reports on the Marijuana Industry? New Data May Surprise You.” [19] Jimenez, A. (Sept 2014) “What Crime is the Largest Source of Laundered Funds?” [20] https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/the-tax-gap. IRS [21] Gale, W. (April 2019) “How big is the problem of tax evasion?” Brookings Institution. [22] https://bsaaml.ffiec.gov/manual [23] Jimenez, A. (May 2020). “Tax Evasion: The Largest Source of Laundered Funds” [24] https://www.fincen.gov/resources/law-enforcement/case-examples/sars-lead-structuring-and-tax-convictions. FinCEN. [25] https://www.ice.gov/doclib/aml/pdf/2010/clark.pdf. ICE. [26] https://www.fincen.gov/resources/law-enforcement/case-examples?field_tags_investigation_target_id=684 [27] Performance Work Statement (PWS) for BSA Data Value Project: FinCEN [28] GAO. (Sept 2020) “Anti-Money Laundering; Opportunities Exist to Increase Law Enforcement Use of Bank Secrecy Act Reports, and Banks’ Cost to Comply with the Act Varied.” [29] “IRS Criminal Division Annual Report 2019”. [30] GAO, pg. 95. [31] Id, pg. 149. [32] https://www.fincen.gov/news/speeches/prepared-remarks-fincen-director-kenneth-blanco-delivered-11th-annual-las-vegas-1 [33] A 2018 Treasury OIG audit on SAR data quality found “of 12,654 SARs file by one institution over the 12 month period evaluated, revealed that the filer spelled the name of the financial institution 85 different ways including several misspellings of the institution’s name.” [34] FinCEN is currently researching this issue via the BSA Value Project.