The overwhelming majority of laundered funds originate from tax evasion, yet there is no SAR category to directly report this crime. Criminal money laundering and tax evasion use the same methods and exhibit similar characteristics to financial institutions.

How much money are we talking about?

The IRS last calculated the federal income “tax gap” which is the amount of taxes owed but not paid in a timely or voluntary manner for tax years 2008-2010. The average tax gap was $406 billion per year during that period. The Brookings Institution estimated that the gap would have reached $560 billion by 2018.

Federal income tax is not the only tax that is evaded. State income tax, sales tax and property tax are also evaded by both individuals and corporations. Estimates of the dollar value for evaded state income tax and other taxes is harder to come by. DSA calculated that about $85 billion in state and local income tax would have been evaded in 2017 if state and local income tax is evaded at the same rate as federal income tax.

In order to evade income tax, the gross income itself must be hidden from government eyes. For example, at the highest tax rate, to evade $1.00 in tax, $2.70 of income would need to be concealed.

Therefore, trillions of dollars of (pre-tax) income would need to be hidden to evade $560 billion in federal income tax.

Putting Tax Evasion Proceeds into Scale with Other Financial Crimes

Imagine a jar with 945 jellybeans with each jellybean representing $1 billion dollars in criminal proceeds. Now imagine that 560 are green jellybeans representing the $560 billion dollars generated each year from federal tax evasion. Picture 85 purple jellybeans to be a proxy for the $85 billion dollars from state and local income tax evasion. 100 jellybeans are black to represent $100 billion in illicit drug trafficking proceeds. Healthcare fraud proceeds appear as 110 yellow jellybeans for the $110 billion dollars in annual healthcare fraud. For those keeping track, we now have accounted for 855 of the 945 jellybeans. The combined proceeds from all other crimes are represented by the 90 red jellybeans.

If you closed your eyes and pulled a jellybean out of the jar, nine out of ten tries would result in a tax evasion (green & purple), drug trafficking (black), or healthcare fraud (yellow) jellybean being drawn. While criminal money laundering gets the attention, it is tax evasion that accounts for the bulk of funds laundered.

Are Funds that Evade Taxes in the Financial System?

Arguably not all funds that evade taxes go through the laundering traditional money laundering process (placement, layering, and integration). Some funds may be part of the informal economy and will not directly enter a financial institution. For example, a housecleaner is paid in cash and uses the cash to purchase groceries.

However research by Gabriel Zucman has found that tax evasion is most often undertaken by the richest households. The richest households also under-report the largest percentages of their income. Andrew Johns and Joel Slemrod found that 63% of under-reporting is associated with taxpayers in the top decile of true Adjusted Gross Income.

Recall, that it is not just the evaded taxes that are hidden, it is the gross income that must be concealed as well. These large dollar amounts of both the gross income and taxes evaded are likely directly integrated into the financial system. Why? First, according to the FDIC, the more you earn, the more likely you are to have a bank account. Secondly, the IRS found that tax under-reporting most often occurs by individuals under-reporting business income (which have bank accounts).

To get an idea of what federal income tax evasion looks like at the highest income levels, consider a household at the top 0.01% income percentile (which was $12,899,070 in 2017) that under-reported income by 25%. The household would have taken measures to hide $3,224,767 of income thereby evading $1,193,163 in taxes.

Are Tax Evaded Funds “Laundered”?

The traditional money laundering steps of placement, layering and integration often occurs when evading taxes. For instance, a state-legal Marijuana Related Business (‘MRB’) may conduct a significant portion of its sales transactions in cash and fail to report all its earned income. The MRB does have a bank account and eventually places some of the unreported cash income into a financial institution. Layering and the use of shell companies has been cited by government officials as a key facilitator of tax evasion and money laundering. Research has found that the top 0.01 percent of wealth-holders evades about 25 percent of its tax liability by concealing assets and investment income abroad. Finally, high net worth tax evaders who conceal assets in offshore accounts integrate the funds into bank deposits, real estate, and invest in bonds, stocks and mutual funds managed by banks on their behalf.

Financial Institutions Look for Money Laundering, Not Limited to Illicit Funds

The FFEIC Manual discusses that banks are not required to determine the underlying crime of a given suspicious activity:

Banks are required to report suspicious activity that may involve money laundering, BSA violations, terrorist financing, and certain other crimes above prescribed dollar thresholds. However, banks are not obligated to investigate or confirm the underlying crime (e.g., terrorist financing, money laundering, tax evasion, identity theft, and various types of fraud). Investigation is the responsibility of law enforcement. When evaluating suspicious activity and completing the SAR, banks should, to the best of their ability, identify the characteristics of the suspicious activity.

The attorneys at Ballard Spahr explain why in most instances, tax evasion is not a predicate crime for money laundering offense (i.e. specified unlawful activity):

The most commonly enforced section of the “transactional” money laundering statute, Section 1956(a)(1), requires the proceeds involved in the transaction at issue to in fact represent the proceeds of “specified unlawful activity” (“SUA”), a defined statutory term which broadly includes many types of criminal conduct. One of the few offenses not included is tax fraud: Congress has defined “SUA” so as to not include tax crimes under Title 26, the Internal Revenue Code.

What are the Characteristics of Suspicious Activity?

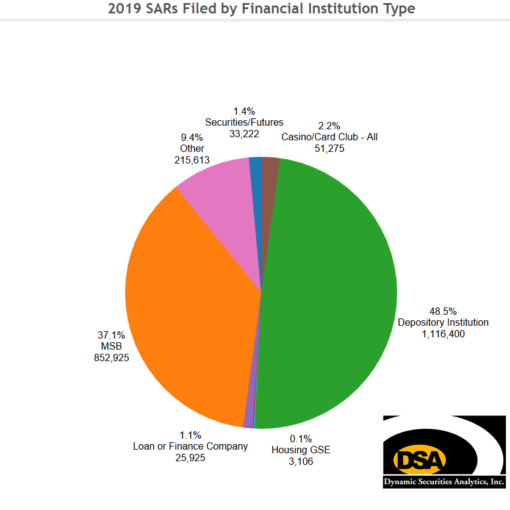

Financial institutions report suspicious activity that could be indicative of money laundering via a Suspicious Activity Report (SAR) form with FinCEN, a Treasury Department agency. The SAR form has 96 different categories of suspicious activity, half of which are not linked to any specific crime. About 3.8 million or 69% of SAR categories checked in 2019 were in the “unspecified crime” group.

Examples of these general or “unspecified crime” suspicious activity categories include:

- Transaction(s) Below BSA Recordkeeping Thresholds

- Transaction with No Apparent Economic, Business, or Lawful Purpose

- Multiple Individuals with Same or Similar Identities

- Refused or Avoided Request for Documentation

- Unknown Source of (casino) Chips

Someone engaging in tax evasion (from a legal source) would use these same techniques and present the same characteristics of suspicious activity as a criminal laundering dirty money. Complex corporate ownership, high risk jurisdictions, transactions without an apparent purpose, and currency transactions below $10,000 are all methods commonly used to evade taxes, and to launder illicit proceeds.

Nevertheless, financial institutions are required to report the “characteristics of the suspicious activity” for a crime (tax evasion) that is not a Specified Unlawful Activity for money laundering. Given the huge dollars involved in tax evasion relative to other crimes, banks must be detecting suspicious activity that is in fact tax evasion at a massive rate. In fact, FinCEN has highlighted SARs that were helpful in tax evasion prosecutions, see examples here, here and here.

For example, 479,496 SARs for “Transaction(s) Below BSA Recordkeeping Thresholds” were filed in 2019. DSA estimates that 326,000 – 407,000 of those SARs could represent individuals attempting to evade taxes.

Financial Institutions Can Report Select Crimes

In addition to the “unspecified crime” suspicious activity, SAR forms list about 47 different specific crimes including:

- Check Fraud

- Elder Financial Exploitation

- Terrorist Financing

- Human Trafficking

- Healthcare Fraud

Financial Institutions Can Not Explicitly Report Tax Evasion or Drug Trafficking

There is no SAR category for tax evasion. Yet about 68% of laundered funds are proceeds from income tax evasion and when the gross hidden income is included, an estimated 85% of all laundered funds are related to tax evasion. Notably, drug trafficking is not a SAR category even though it is a National Priority.

Circling back to the jellybean analogy, when a financial institution puts its hand into the jar of suspicious criminal proceeds, it would rarely pull anything other than tax evasion and drug trafficking.

Does it make sense that financial institutions are unable to directly report tax evasion and drug trafficking on SARs?

What are we gaining from filing generic SARs on tax evasion and drug trafficking? More importantly, what insights are we losing?

The analysis and comparisons of illicit proceeds is limited to funds generated in the US. For example, if a person evaded taxes in another country and transferred those funds to the US, these funds would be excluded from the calculations. Similarly, funds embezzled in another country and wired to the US are not included.