Summary: Offshore crypto exchanges aren’t as “offshore” as they would like regulators to think. US users of FTX.com have funds frozen on the offshore exchange. US regulators should analyze the +100,000 Unregistered MSB SARs to identify offshore crypto exchanges that provide services to Americans.

Consider these facts:

- Offshore crypto exchanges account for the vast majority of crypto transactions.

- Residents of large economies including the US and China are not supposed to trade on the offshore exchanges.

How can the biggest crypto exchanges exclude the biggest economies?

Answer: They don’t. The numbers just don’t add up.

Benefits to Crypto Exchanges of being Offshore

Crypto exchanges see multiple benefits to operating offshore. High among the benefits are:

- Avoiding costly regulatory obligations

- Offering crypto products that may be prohibited onshore such as crypto futures, crypto derivatives, and securities tokens

- Granting traders much higher margin ratios than onshore equivalents.

The WSJ found:

By operating outside of the U.S. and not serving American clients, [crypto] exchanges can avoid numerous CFTC rules, including investor-protection requirements and safeguards against money laundering and market manipulation.

As highlighted above, the key to operating an offshore crypto exchange is “not serving American clients.”

When does offshore become onshore?

The CFTC spells out when foreign entities need to register with the agency:

If you live in the United States, foreign entities that solicit you to trade are generally required to register with the CFTC; however, some non-U.S. firms are exempt from registration.

And

Products that use virtual currencies as the underlying commodity are regulated by the CFTC. Intermediaries that advise clients regarding virtual currency commodity futures or that facilitate trading in those instruments must be registered with the CFTC and NFA.

Offshore crypto exchanges also engage in spot trading. Spot trading can have implications involving securities laws and MSB registration.

The CFTC notes:

Digital currency spot market trading companies are considered money service businesses (MSB) by the U.S. Treasury and must be registered with Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN). Many states also require virtual currency trading websites to register as money transfer companies.

In May 2019, FinCEN advised that offshore crypto companies, even with no physical presence in the U.S., may need to register with FinCEN:

Many business models of entities dealing with CVC [Convertible Virtual Currency] operate as money transmitters. As money transmitters, persons accepting and transmitting CVC are required, like any money transmitter, to register with FinCEN as MSBs and comply with anti-money laundering/countering the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT) program, recordkeeping, and reporting requirements.

These requirements apply equally to domestic and foreign-located CVC money transmitters doing business in whole or substantial part within the United States, even if the foreign-located entity has no physical presence in the United States.

When does a foreign-located MSB/ offshore crypto exchange need to register with FinCEN?

Relevant factors include whether the foreign-located person, whether or not on a regular basis or as an organized or licensed business concern, is providing services to customers located in the United States.

FinCEN’s Acting Director warned:

We will hold accountable foreign-located money transmitters, including virtual currency exchangers, that do business in the United States when they willfully violate U.S. anti-money laundering laws.

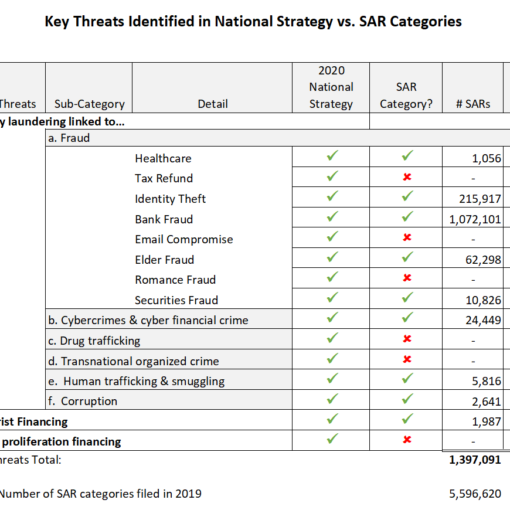

Unregistered Crypto Exchange SARs

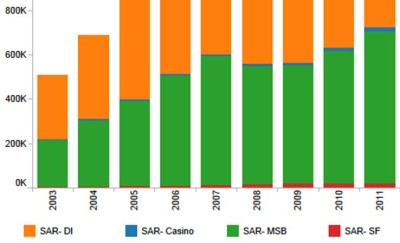

DSA previously found that San Francisco based registered crypto exchanges filed tens of thousands of Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs) involving suspected Unlicensed or Unregistered MSBs. My analysis noted:

Cryptocurrency exchanges filed thousands of unregistered cryptocurrency exchange SARs in 2021. The good news is that the registered cryptocurrency exchanges are detecting unregistered cryptocurrency exchanges. The bad news is that the horde of unregistered cryptocurrency exchanges are likely non-compliant with AML obligations.

“Unregistered Cryptocurrency Exchange SARs Skyrocket in 2021”, Dec 2021.

Onshore crypto exchanges have insight into the source and destination of customer funds and tokens. From January 2020 through October 2022, over 108,000 Unlicensed or Unregistered MSB SARs have been filed by San Francisco-based crypto exchanges. I suspect that a good number of these SARs identify Americans who trade crypto offshore then transfer tokens to the US exchanges to cash out to fiat.

U.S. regulators should query the SAR database for Unlicensed or Unregistered MSB SARs to identify offshore crypto exchanges that are ‘providing services to customers located in the United States‘.

Are Offshore Crypto Exchanges Turning Away Customers?

Generally, if a cryptocurrency exchange wants to avoid a country’s regulations, they need to avoid customers from that country. For example, if an offshore crypto exchange wants to avoid US regulations, it should implement policies and procedures to prevent US users from opening accounts.

A prescient article by Roger Parloff in Yahoo Finance from August 2021 reported:

In hopes of evading U.S. regulators, the offshore exchanges, including FTX, all say they refuse orders from U.S. customers. But such “geofencing” is notoriously hard to do in a world with virtual personal networks (VPNs) and other workarounds, and there’s evidence that at least some exchanges haven’t always tried very hard.

The Wall Street Journal also discussed in July 2021 whether offshore exchanges were effectively preventing Americans from accessing the platforms:

Americans can access offshore crypto exchanges by using virtual private networks, tools that can be used to mask the country where an internet user is based. Many crypto websites and online forums feature information on using VPNs to access non-U.S. exchanges.

U.S. traders can also slip past user-identity checks that aim to filter out Americans, sometimes by lying about where they are from. At FTX, for instance, until this week [July 30, 2021] users signing up for the lowest level of trading access only needed to provide their names, emails and country of residence, with no requirement to provide documents to confirm their identity.

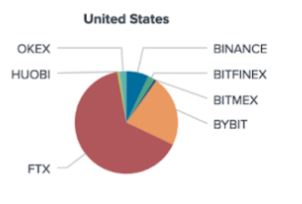

The WSJ article relied on an Inca Digital study that geotagged crypto traders and the exchanges they used. The study found that FTX.com was the offshore exchange most often used by U.S. crypto derivative traders. Bybit was second and Binance was in third place.

Offshore Exchange used by US Crypto Derivative Traders

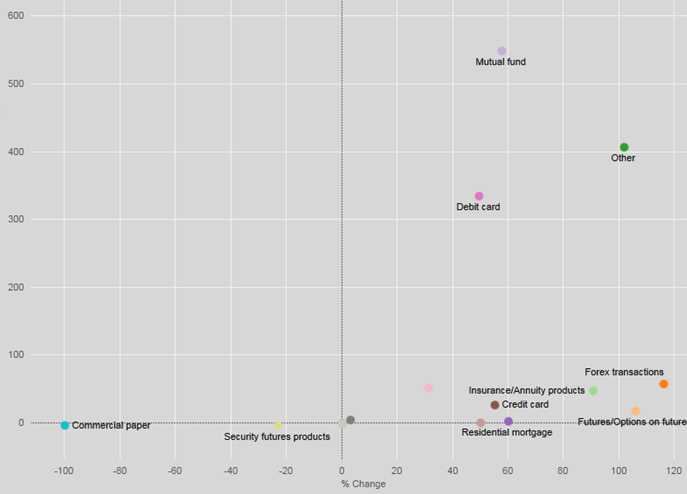

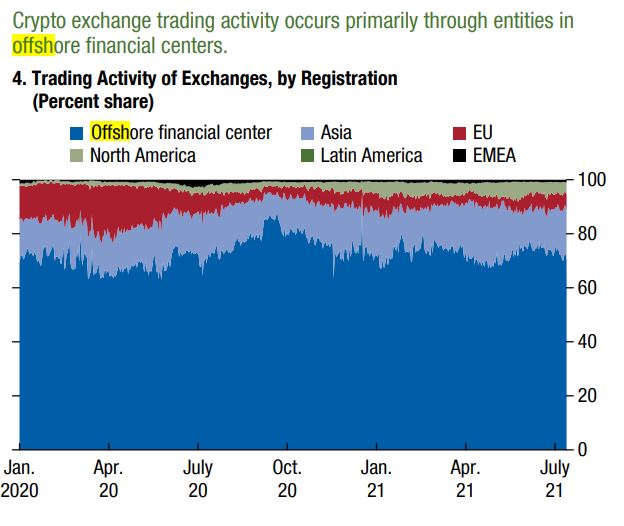

The issue of offshore trading is not limited to derivative trading. Spot trading also largely occurs offshore. The IMF found that the majority of crypto exchange trading occurs via offshore and Asian exchanges.

IMF Study on Crypto Exchange Location & Trading Percentage

Coinbase CEO, Brian Armstrong, recently opined:

American consumers and advanced traders alike have been engaging with risky, offshore platforms outside the jurisdiction — and protection — of U.S. regulators. Today, more than 95% of crypto trading activity happens on overseas exchanges.

Another country that offshore crypto exchanges, on paper, should avoid is China, which banned all cryptocurrency trading in 2021. Yet, China ranked second worldwide in crypto transaction volume.

Chainalysis noted:

This is especially interesting given the Chinese government’s crackdown on cryptocurrency activity, which includes a ban on all cryptocurrency trading announced in September 2021. Our data suggests that the ban has either been ineffective or loosely enforced.

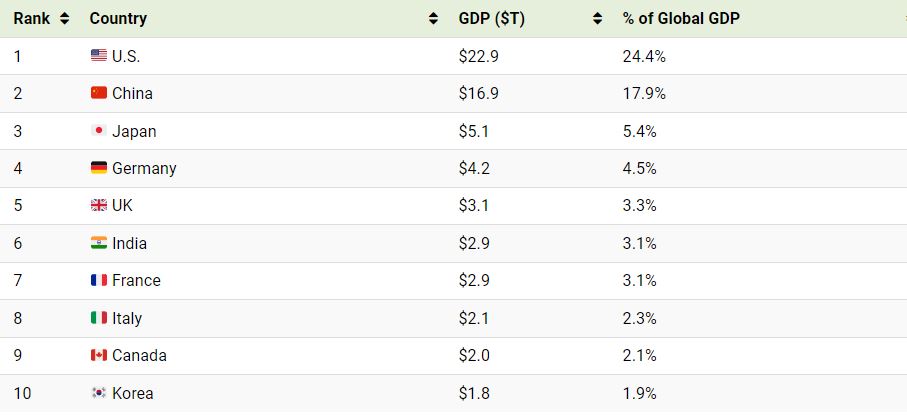

The US and China combined account for 42% of global GDP. Even if other countries have larger crypto adoption rates, they have far fewer assets to invest in crypto. The numbers just don’t add up.

Largest Countries by GDP

Who Else Evades Detection at Offshore Crypto Exchanges?

If offshore crypto exchanges can’t detect and prevent American crypto traders from opening accounts, what are the odds that they will also “miss” North Koreans, Iranians, ransomware gangs, drug traffickers, and darknet markets using VPNs and false countries of residence?

Who were FTX.com Customers?

A FTX bankruptcy declaration by its new CEO John J. Ray states:

The FTX.com platform is not available to U.S. users.

Despite the CEO’s claims that FTX.com was “not available to U.S. users” and that FTX expressed a “willingness to keep American traders off its Bahamas-based exchange”, several U.S. users announced that they had funds stuck in FTX.com.

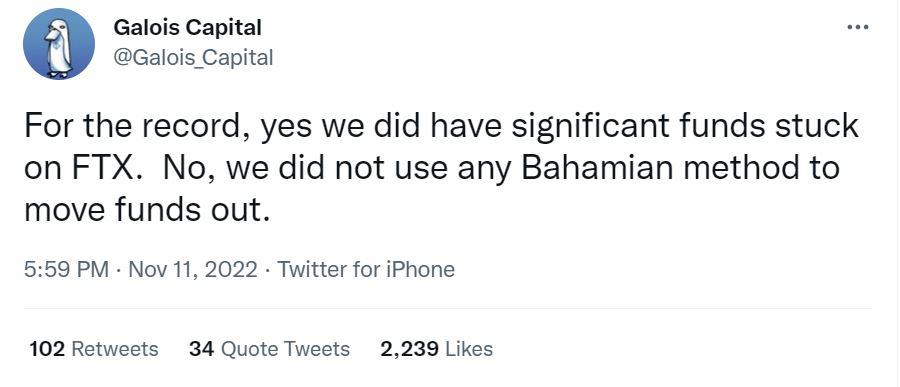

Galois Capital appears to be located in US, yet they tweeted that they had funds at FTX:

The “Bahama method” would only have applied to funds held at FTX.com, not FTX.us.

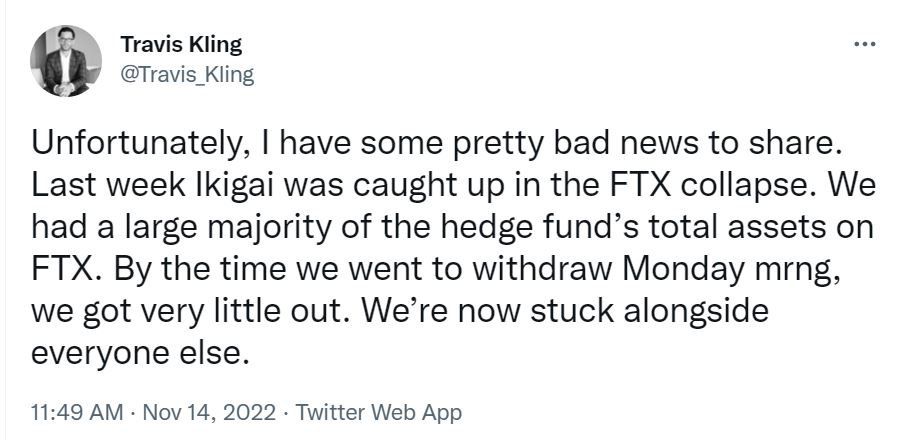

Another US-based hedge fund, Ikigai Asset Management, also had a “large majority” of its funds on FTX and was unable to get its money out. Ikigai did not specify if they meant FTX.com or FTX.us.

Crypto lender BlockFi, incorporated in Delaware and operating out of New Jersey, stated:

We do have significant exposure to FTX and associated corporate entities that encompass obligations owed to us by Alemeda, assets held at FTX.com, and undrawn amounts from our line of credit.

Axios reports “Genesis, like many other crypto firms, held digital assets on FTX.com”. US-based Genesis crypto lending unit froze withdrawals.

Gemini, not to be confused with Genesis, also “paused withdrawals”. This appears to be due to Genesis “powering” Gemini’s yield-generating Earn program. Genesis’ frozen funds on FTX.com therefore spilled over to Gemini, yet another US based company.

The Roger Parloff article also raised the question directly with Sam Bankman-Fried on how FTX.com could deal with Alameda which was based in Berkely, CA:

Alameda’s role at FTX invites at least two followup questions, however. One is: If Alameda is based in Berkeley, how could it be dealing with FTX? I thought FTX didn’t accept trades from U.S. customers.

“Yeah, it’s an interesting question,” Bankman-Fried responds. “The answer is that [Alameda Research] is not a U.S. entity at this point. Its operations are not generally in the U.S.”

When did it switch?

“A couple years ago. Before FTX was founded.”

Does it still have offices in Berkeley?

“It doesn’t have a substantial office there.”

Where is it based now?

“So part of the answer is that it’s a bit distributed. Especially during COVID, it’s been the case that people will get stranded in various places for months to a year. . . . But it’s been predominantly Asia-based for the last few years.”

Where is its charter?

“BVI.”

Indeed, around the time FTX launched in 2019, a British Virgin Islands entity was formed called Alameda Research LTD. But the Delaware entity, Alameda Research LLC is still in “good standing,” according to Delaware authorities. So is a newly formed entity called Alameda Research Holdings Inc., which was just incorporated in Delaware two months ago. How are they all related?

In response to an email seeking clarification, he writes, without further elaboration, “BVI is a subsidiary of LLC.”

FTX bankruptcy filings indicate that Alameda Research LLC is incorporated in Delaware.

Parloff also questioned SBF about other customers trading on FTX.com:

What about all the other large asset managers who now provide liquidity to FTX? Who are they and where are they based?

“So obviously, I don’t want to give away specific client information,” he says in an interview, “but in general when you look at the largest trading firms in the world . . . most of them have non-U.S. teams.

Was FTX.com truly offshore?

FTX.com creditors list will likely show who was trading on the offshore platform. Depending on the location of the users, it will be interesting to see if FTX.com met FinCEN’s MSB threshold of doing “business wholly or in substantial part within the United States.” We may also be able to see if FTX.com met the CFTC’s criteria for registering with the US derivatives regulator.