Summary: But for the ability to monetize CSAM through cryptocurrency, both the amount of CSAM and the number of children exploited would be lower.

DSA has published a whitepaper titled “How Cryptocurrency Revitalized Commercial CSAM.” The whitepaper explores the intersection of cryptocurrency with commercial Child Sexual Abuse Material (CSAM) and financially motivated sextortion of minors.

DSA has published a whitepaper titled “How Cryptocurrency Revitalized Commercial CSAM.” The whitepaper explores the intersection of cryptocurrency with commercial Child Sexual Abuse Material (CSAM) and financially motivated sextortion of minors.

While it is widely understood that cryptocurrency is used as a means of payment for online CSAM, the role of cryptocurrency in revitalizing commercial CSAM has not previously been examined in detail.

Download the whitepaper “How Cryptocurrency Revitalized Commercial CSAM” here.

Key Take-Aways

- Commercial online CSAM was constrained from the late 2000’s through the late 2010’s as traditional payment methods were curtailed.

- The introduction of cryptocurrency as the payment method for CSAM contributed to the dramatic increase in online commercial CSAM.

- Cryptocurrency features including pseudo-anonymity, cross-border transactions, speed, and decentralization are valued by CSAM producers and consumers.

- Commercial CSAM market structure incentivizes new content, thereby increasing the number of children exploited.

- Financially motivated sextortion of minors is a rapidly growing threat that relies on cryptocurrency to remit profits across international borders.

An online version of the whitepaper is available below.

How Cryptocurrency Revitalized Commercial CSAM

“Bitcoin has been used to monetize the production of child exploitation material—a development rarely seen before the rise of cryptocurrency.”

– U.S. Department of Justice[i]

Overview

Child sexual abuse material (CSAM) has existed online for decades. Yet, it was not until the introduction of cryptocurrency as a means of payment did the production and sale of CSAM become an increasingly commercial activity. The recent explosion in financially motivated sextortion of children has added a harrowing new dimension.

The commercialization of online child sexual abuse material required methods to anonymize participants’ (1) involvement in producing and/or consuming CSAM, and (2) payments. The internet, in conjunction with Tor and end-to-end encrypted messaging, solved the first issue. Cryptocurrency solved the latter.

Like Baseball Cards

Prior to cryptocurrency, CSAM was primarily swapped amongst consumers in what child sexual exploitation investigators described as “baseball card trading.”[ii] CSAM trading guaranteed mutually assured destruction, thereby creating equal risk between participants. The practice also avoided leaving a money trail for investigators to follow.

Importantly, pre-cryptocurrency, the creators of child sexual abuse material were largely limited to those with an interest to “trade and share images of their own sexual exploits with like-minded people” since there was not a robust commercial market.[iii] Cryptocurrency removed the constraint on the number of potential CSAM producers by facilitating commercial CSAM and financially motivated sextortion of minors. That change shifted the primary driver of CSAM production from the desire to consume the material to making money off those consumers.

Early Internet Days

Many early internet users believed that their browsing was anonymous. In several cases, individuals created surface websites selling CSAM and accepted payment via credit card. In 1999, a multi-government agency investigation found that a Texas company operated a commercial child pornography website conglomerate that earned over $1 million per month.[iv] In a second case, Regpay, a Belarus-based company, provided credit card processing services to hundreds of commercial CSAM websites and operated their own CSAM sites.[v] Regpay processed between $2.5 and $7 million in credit card sales for CSAM websites. They contracted with a Florida company, Connections USA, to access a merchant bank in the United States.[vi]

In response to this and other cases, a coalition of credit card issuers and other financial institutions convened to prevent credit cards from being used for commercial CSAM, and they have reportedly been mostly eliminated as a payment method.[vii] The curtailing of credit card payments left commercial CSAM moribund.

Anonymized Internet Activity and Encrypted Communications

Anonymized online activity via Tor and the dark web created new ways for CSAM producers and consumers to share and trade child exploitation material. Similarly, while end-to-end encryption ensures privacy and security of communications in community forums, chat rooms, and messaging, it also provides a safe haven for CSAM offenders.

Still, the dark web and encrypted communications did not lead to the mass commercialization of online child sexual abuse material. For example, a 2015 European law enforcement study noted that only 7%–10% of online CSAM was estimated to be commercial.[viii]

Dark markets (hidden marketplaces only accessible via Tor) continued to encounter the issue of payment methods being linked back to an individual’s identity, which likely thwarted the commercialization of CSAM.

CSAM and Early Digital Currency

An early attempt to use anonymized digital currency payments to facilitate commercial CSAM involved Liberty Reserve.[ix] Founded in Costa Rica in 2006, the company operated a digital currency called “LR,” which was a centralized, non-cryptographic (i.e., did not use a blockchain or cryptography) digital currency pegged to the U.S. dollar.

LR users could remain anonymous during transactions with other LR users, merchants accepting LR, and even Liberty Reserve itself as third-party money exchangers were used to on- and off-board customer funds. However, when U.S. law enforcement shut down Liberty Reserve for a variety of money laundering violations, including processing payments for child pornography, the LR digital asset was also shuttered.

Anonymous Online Activity + Cryptocurrency = CSAM Commercialization

The introduction of cryptocurrency as a payment method removed the last remaining barrier to the mass commercialization of CSAM. With the advent of cryptocurrency used in conjunction with other anonymizing techniques, offenders could anonymously exchange and pay for CSAM. A June 2023 United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime report noted that cryptocurrency payments had “unfortunately lead to the revival in the commercialization of CSAM online.”[x]

Why Cryptocurrency?

When a bad actor wants to conduct a financial transaction, they will assess whether a financial product can move funds far, fast, in large amounts, irreversibly, anonymously, and to a third-party.[xi] Cryptocurrency is attractive to those involved in commercial CSAM because it has all the features they value in one financial product.

CSAM cryptocurrency transactions move seamlessly across international borders (far) and can be settled in minutes (fast). There is no cap on the value of cryptocurrency that can be transferred in a transaction (in large amounts). In most instances, a cryptocurrency transaction cannot be reversed once it has been added to the blockchain (irreversibly). Cryptocurrency wallets are pseudonymous, meaning the true owner of the wallet may never be linked to a given wallet address (anonymously), and the same can be true for the recipient (to a third-party).

Some have argued that public blockchain ledgers and blockchain analytics make cryptocurrency a poor vehicle for illicit finance. However, most cryptocurrency transactions occur off the blockchain within private cryptocurrency-exchange ledgers, thereby evading blockchain analytics; bad actors employ multiple methods to obfuscate on-chain activity; and attributing a crypto wallet address to an actual person remains on ongoing challenge.

CSAM Adopts Cryptocurrency to Commercialize

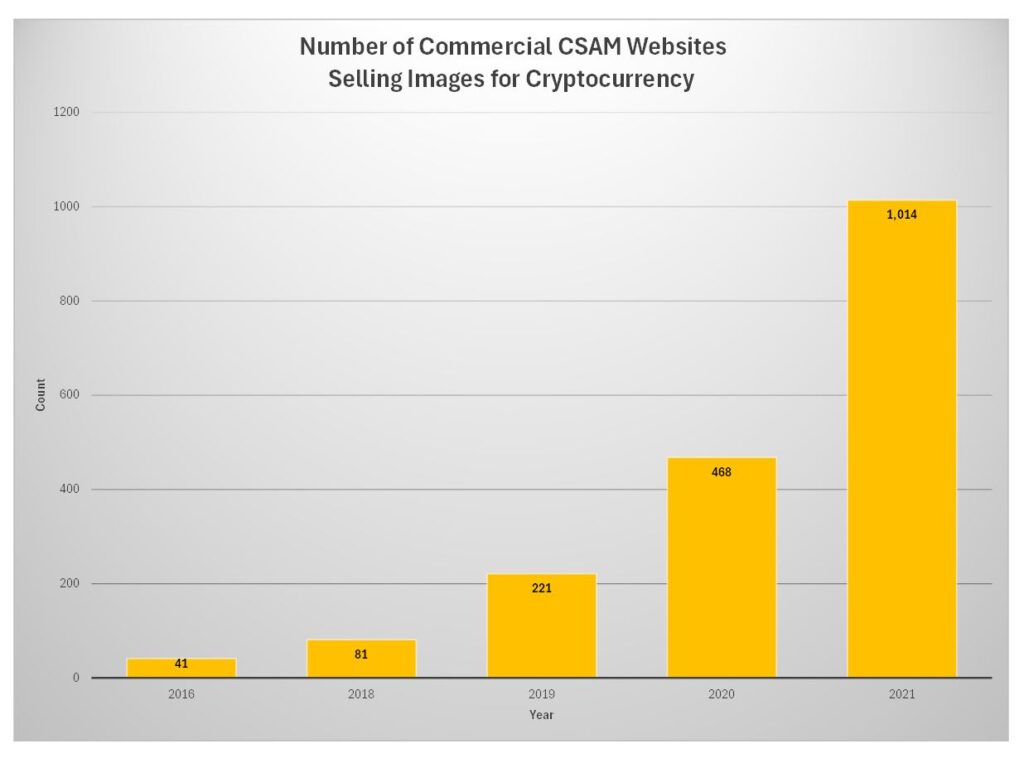

As the Human Trafficking Front explains, CSAM has evolved from “nonsalable to commercial.”[xii] In 2021, the Internet Watch Foundation (IWF) determined that 70% of newly discovered dark web CSAM distribution services were commercial.[xiii] In addition, IWF reported that the number of commercial CSAM sites selling images for cryptocurrency grew from 41 in 2016 to 1,014 four years later.

Figure 1. Data from Internet Watch Foundation.[xiv] Graphic prepared by Dynamic Securities Analytics, Inc.

With the commercialization of CSAM, producers of content broadened from child pornography consumers looking to trade, to anyone with a profit motive. For example, the Department of Justice notes that commercial virtual child sex trafficking, which refers to livestreaming abuse of children over the internet in exchange for money, appears to frequently be generated in the Philippines, where knowledge of English and the widespread availability of high-speed internet facilitate communication and poverty motivates using children to acquire money.[xv]

Similarly, the relatively high financial rewards available to organizers of live, distant child abuse in developing countries is a significant driver of its widespread proliferation. By contrast, the buyers of virtual child sex trafficking typically reside in wealthier countries like the United States or the UK.[xvi] Therefore, virtual child sex trafficking payments need to be remitted across international borders, and many participants turn to cryptocurrency.

Finally, commercial CSAM producers and marketplace administrators use cryptocurrency to pay for their digital infrastructure including servers, virtual private networks, and hosting services.[xvii] The pseudonymity offered by cryptocurrency also enabled traditional online revenue models such as affiliate marketing, ad revenue, and web-based commissions related to commercial CSAM.[xviii] In 2022, the Internet Watch Foundation identified “invite child abuse pyramid” (ICAP) sites that incentivize users to spam links to CSAM sites which benefit criminals from via increase web traffic and additional CSAM purchases.[xix]

Commercial CSAM Case Studies

Case Study 1

Welcome to Video

Welcome To Video offered CSAM videos for sale via bitcoin. Users could also upload new and unique videos in exchange for credits to view other videos. This way, Welcome To Video encouraged the production of new CSAM content, which the organizer could sell for a profit.[xx] In fact, the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC) determined that 45 percent of examined videos contained images that had not been previously known to exist.[xxi] Law enforcement determined that more than $350,000 worth of bitcoin flowed into the Welcome To Video wallet address between 2015 and 2018.[xxii]

Case Study 2

DarkScandals

DarkScandals, which operated from 2012 until 2020, was another commercial website offering CSAM material. Per the Department of Justice and similar to Welcome To Video’s business model, “users could allegedly access the illicit content by paying cryptocurrency or uploading new content.” Notably, DarkScandals turned to cryptocurrency after PayPal blocked the website from its payment network.[xxiii]

The U.S. government filed civil forfeiture action seeking recovery of illicit funds from 303 virtual currency accounts allegedly used by customers to fund DarkScandals and to promote child exploitation. DarkScandals earned almost $2 million in bitcoin through commercialized CSAM.[xxiv]

Suspected CSAM Cryptocurrency Transactions

Suspicious Activity Report CSAM Analysis

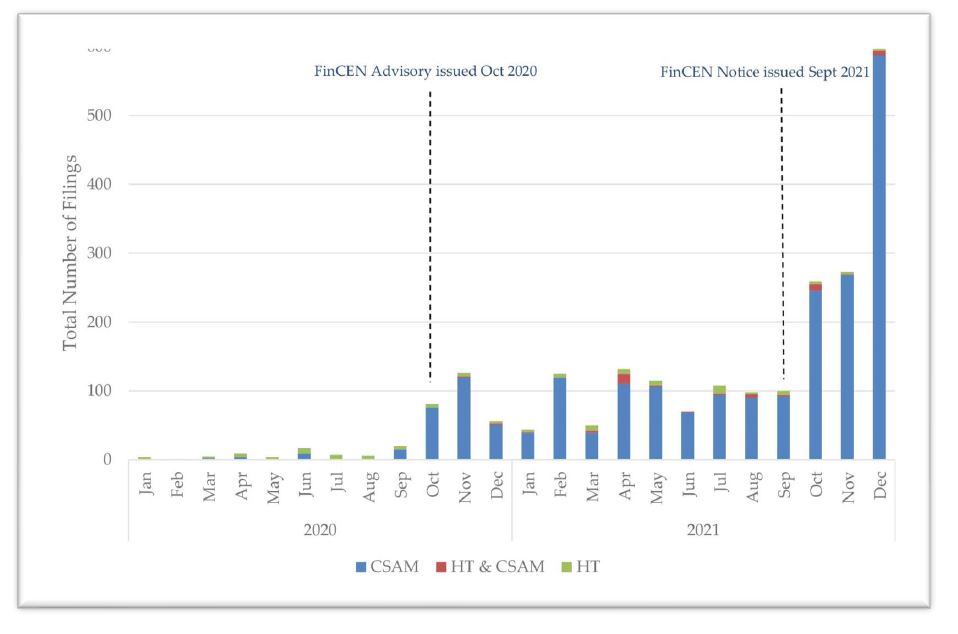

U.S. financial institutions including banks, money-services businesses, and cryptocurrency exchanges are required in certain instances to file reports about suspicious activity with FinCEN, a bureau of the Treasury Department. In 2021, FinCEN reported that cryptocurrency “is increasingly the payment method of choice for OCSE [online child sexual exploitation] offenders who make payments to websites that host CSAM.”[xxv]

Earlier this year, FinCEN examined reports of cryptocurrency use in suspected commercial online child sexual exploitation that also identified suspected human trafficking.[xxvi] FinCEN noted that most of the incidents involved either customers purchasing CSAM or vendors exchanging cryptocurrency proceeds generated from CSAM sales for fiat currency (e.g., dollars).

FinCEN identified several ways cryptocurrency (almost exclusively bitcoin) was used in suspected online child sexual exploitation transactions. Purchasers used bitcoin ATMs to send payment to CSAM vendors or purchased CSAM materials directly on dark markets. Commercial CSAM vendors attempted to obfuscate the illicit nature of their cryptocurrency by using crypto mixing services to intermingle coins from different transactions, or decentralized finance apps to swap one type of virtual currency for another. Additionally, the use of cryptocurrencies with enhanced privacy features, such as Monero, may have prevented financial institutions from detecting commercial CSAM transactions altogether.

The number of suspicious activity reports involving cryptocurrency and CSAM grew from 336 in 2020 to 1,976 in 2021.

Figure 2: Number of OCSE- and Human Trafficking-Related BSA Reports Involving CVC by Year ad Type. Image from FinCEN.[xxvii]

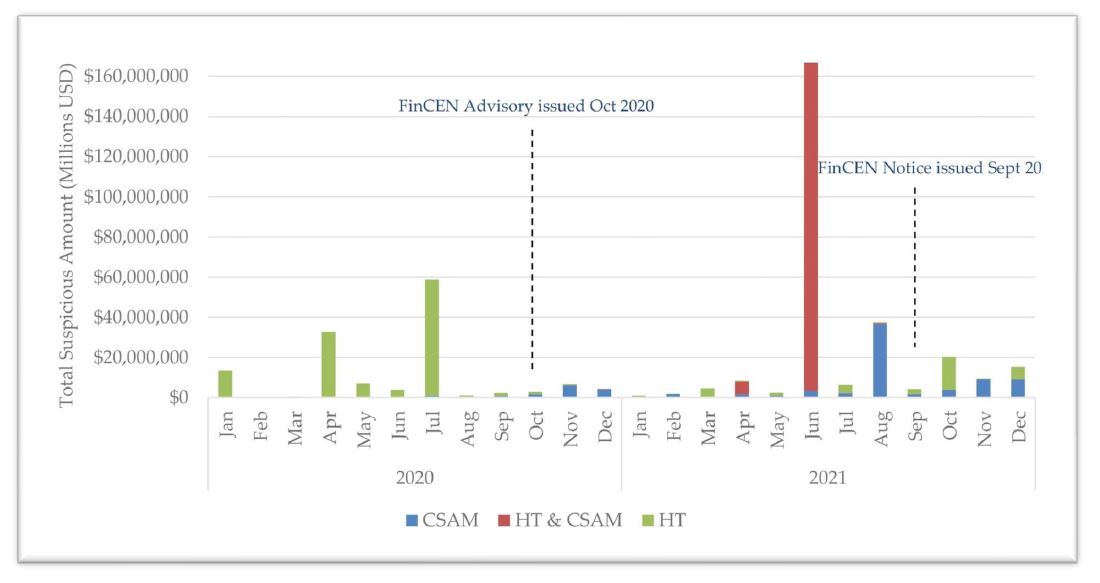

The total value of the suspected online child sexual exploitation financial transactions using cryptocurrency in 2020 and 2021 was $411 million. Individual transaction amounts varied widely, ranging from less than $100 to several transactions over $1 million. On the high end, one suspected marketplace used for CSAM distribution had cryptocurrency transactions totaling $163 million; however, it is unclear if that amount includes proceeds for other illicit activities (e.g., drug sales) occurring in the marketplace.

Figure 3: Total Value of OCSE- and Human Trafficking-Related BSA Reports Involving CVC by Year and Type. Image from FinCEN. [xxviii]

Some blockchain analytics vendors have identified just a fraction of the transaction volume reported to FinCEN. For example, TRM tracked $3.81 million in crypto to CSAM-linked entities in 2022,[xxix] and Chainalysis found less than $3 million in total cryptocurrency value sent to CSAM sites from 2015 through 2020.[xxx] On the other hand, a representative from the Anti-Human Trafficking Intelligence Initiative stated that they identified a single individual who had received cryptocurrency payments valued over $100 million for online CSAM.[xxxi]

There are several possible explanations for the large variance between CSAM suspicious activity reporting transaction dollar values and the values identified by blockchain analytics. The difference may reflect off-chain transactions outside of the scope of analytics firms, Know Your Customer and other information available to financial institutions that facilitate identification of CSAM, and divergent standards for classifying a transaction as suspicious versus conclusively illicit. Additionally, blockchain analytics vendors differ in CSAM subject matter expertise, methodologies, and blockchains examined.

Regulatory Actions Involving Suspected CSAM Transactions

Moreover, FinCEN’s suspected CSAM transactions volumes only reflect reports filed by financial institutions complying with their regulatory obligation. Several cryptocurrency companies, including U.S.-based cryptocurrency exchanges, crypto mixers, and bitcoin ATMs, have faced regulatory sanctions noting suspicious activity relating to CSAM.[xxxii]

For example, Binance, the largest cryptocurrency exchange in the world, did not file any suspicious activity reports on any topic with FinCEN until at least October 2022. In November 2023, FinCEN imposed a $3.4 billion civil penalty on Binance and noted in the Consent Order (emphasis added):[xxxiii]

FinCEN observed over a thousand direct bitcoin and ether transactions, worth hundreds of thousands of dollars, with child exploitation-associated CVC wallet addresses, including at least three separate marketplaces dealing in child sexual abuse materials (CSAM).

Next, the New York Department of Financial Services’ Consent Agreement with Coinbase discussing the firm’s transaction monitoring system backlog states (emphasis added):[xxxiv]

The Department has identified troubling examples of suspicious conduct that should have been identified, stopped, and (in some cases) reported to the authorities but was not, at least initially, due to the backlog. This includes, among other things, examples of possible money laundering, suspected CSAM-related activity, and potential narcotics trafficking.

In a third case, involving Bittrex, FinCEN noted in the Consent Order (emphasis added):[xxxv]

The suspicious transactions involved various types of illicit activity, including direct transactions with online darknet marketplaces such as AlphaBay, Agora, and the Silk Road 2. These markets are use to buy and sell contraband such as stolen identification data, illegal narcotics, and child pornography.

Sextortion of Minors and Cryptocurrency

CSAM produced by adult offenders is not the only commercial use of online child sexual exploitation material. The harrowing crime of financially motivated sextortion of minors is rapidly escalating.

The Department of Justice’s 2016 National Strategy for Child Exploitation Prevention and Interdiction discussed sextortion at length without a single mention of financially motivated predators.[xxxvi] In 2023, the Department of Homeland Security estimated that 79% of sextortion of minors is for financial gain as opposed to sexual gratification.[xxxvii]

Financially motivated sextortion of minors is a crime in which an offender coerces a minor to create and send sexually explicit images or video. U.S. law defines “Offense Involving Child Pornography” to include the production of child pornography where offenders use deceit or non-physical forms of coercion, such as blackmail, to acquire child pornography depicting the targeting of minors.

Sextortion offenders often connect with teenage male victims through social media, online games, and messaging apps by creating profiles that appear to be young women. The FBI reports that predators may hack or purchase social media accounts known to a victim or create copycat accounts to appear as if they are someone the victim already knows. While posing as teenage girls (such as by using face-filter apps or recorded video), the predator secretly records explicit video calls with children or asks them to send sexually explicit pictures. After receiving sexually explicit content from a child, the offender threatens to release the material to friends, family, schoolmates, and/or social media followers unless the victim provides payment.

There is a potential secondary market for the images on commercial CSAM markets. The Internet Watch Foundation’s CEO, Susie Hargreaves, told the Guardian, “Ten years ago we hadn’t seen self-generated content at all, and a decade later we’re now finding that 92% of the webpages we remove have got self-generated content on them. That’s children in their bedrooms and domestic settings where they’ve been tricked, coerced, or encouraged into engaging in sexual activity which is then recorded and shared by child sexual abuse websites.”[xxxviii]

The FBI and Homeland Security Investigations received over 13,000 reports of online financial sextortion of minors from October 2021 to March 2023. By comparison, NCMEC only received approximately 100 cyber tips involving financially motivated sextortion of children from October 2013 through April 2016.[xxxix]

At least twenty teenage sextortion victims have committed suicide from 2021 to 2023.[xl] The FBI has also identified revictimization scams where for-profit companies charge teen sextortion victims thousands of dollars for “assistance,” use deceptive tactics to elicit payments, and were directly or indirectly involved in the sextortion scheme itself.[xli]

Child victims make sextortion payments to offenders via methods that teens commonly interact with such as mobile apps like Cash App, Venmo, Apple Pay, and Zelle. Sextortion payments have also involved gift cards, wire transfers, credit cards, and cryptocurrency. Children have also been coerced into acting as money mules with sextortion payments from other victims deposited into accounts in their name. The victim/money mule then converts the pooled funds into cryptocurrency to remit overseas to their tormentors.[xlii]

Offenders who engage in financially motivated sextortion of minors are often located outside of the United States—primarily in West African countries such as Nigeria and Ivory Coast, or Southeast Asia. Financially motivated sextortion is also undertaken by transnational criminal organizations that conduct other cyber/crypto crimes like business email compromise and romance scams.[xliii] Sextortion offenders then use cryptocurrency exchanges or cryptocurrency peer-to-peer services to convert the cryptocurrency into local currency.

Financially Motivated Sextortion of Minors Case Study

United States v. Olamide Oladosu Shanu

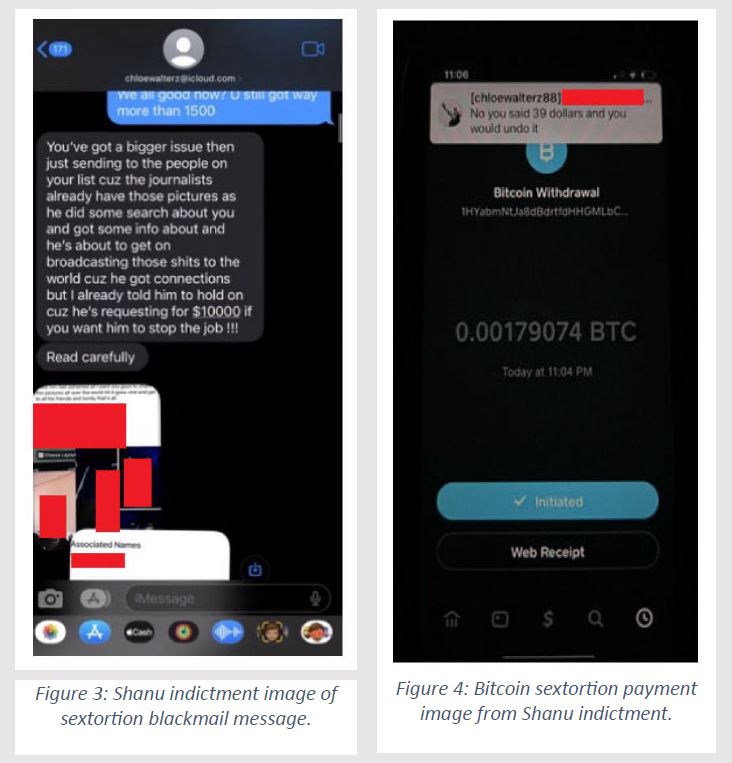

In November 2023, Olamide Shanu, a Nigerian national, and four co-conspirators were indicted in a sextortion scheme on charges including extortion, cyberstalking, and conspiracy to commit money laundering.[xliv]

The indictment alleges that Shanu and co-conspirators used fake and stolen online accounts to contact various males (both children and young adults), typically through Instagram and other social media platforms. The conspirators persuaded the victims to send sexually explicit images of themselves; once in possession of the material, they blackmailed victims into making payments through various peer-to-peer applications.

The conspirators then used money mules, who were typically also victims of the sextortion scheme, to launder the sextortion payments by transmitting the illicit proceeds to the conspirators as cryptocurrency through bitcoin ATMs and Cash App. More than $2.5 million in bitcoin payments from victims were deposited and later withdrawn from a Binance account over the course of three years.

For context, if the average victim paid $500 then this single indictment would reflect approximately 5,000 paying victims.

Conclusion: The Cryptocurrency/ Commercial CSAM Flywheel

Cryptocurrency is the payment method of choice for online child sexual exploitation.

Cryptocurrency facilitates pseudonymous, irreversible, decentralized, cross-border CSAM payments. The commercialization of CSAM has the knock-on effects of driving new content creation and thereby creating new child sexual exploitation victims.

Online child sexual exploitation is accelerating at a devastating rate because of dark market incentives that encourage fresh CSAM and sextortion offenders increasingly seeking out new teen victims.

But for the ability to monetize CSAM through cryptocurrency, both the amount of CSAM and the number of children exploited would be lower.

________________________

Notes

[i] “Report of the Attorney General’s Cyber Digital Task Force” (US Department of Justice, 2020), https://www.justice.gov/cryptoreport.

[ii] Andy Greenberg, Tracers in the Dark: The Global Hunt for the Crime Lords of Cryptocurrency (New York, NY: Doubleday, 2022).

[iii] “Child Sexual Abuse Material: Model Legislation & Global Review” (International Centre for Missing & Exploited Children, 2018), https://www.icmec.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/CSAM-Model-Law-9th-Ed-FINAL-12-3-18.pdf.

[iv] “Towards Zero: An Initiative to Reduce the Availability of Child Sexual Abuse Material on the Internet” (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2023), https://www.unodc.org/pdf/criminal_justice/endVAC/EGM/EGM_CSAM_Removal_Background_Paper.pdf.

[v] “The National Strategy for Child Exploitation Prevention and Interdiction: A Report to Congress” (U.S. Department of Justice, 2010), https://www.justice.gov/psc/docs/natstrategyreport.pdf.

[vi] Alice S. Fisher, “Sexual Exploitation of Children over the Internet: What Parents, Kids and Congress Need to Know about Child Predators” (U.S. Department of Justice, 2006), https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/criminal-ceos/legacy/2012/03/19/AAG Testimony 5032006.pdf.

[vii] Credit cards have been used as a payment method on primarily adult pornography websites that also allegedly contained CSAM material. See Michelle Celarier, “Bill Ackman Sent a Text to the CEO of Mastercard. What Happened Next Is a Parable for ESG.,” Institutional Investor, June 16, 2021, https://www.institutionalinvestor.com/article/2bswuu1nfc040ho7ghudc/culture/bill-ackman-sent-a-text-to-the-ceo-of-mastercard-what-happened-next-is-a-parable-for-esg.

[viii] “Commercial Sexual Exploitation of Children Online: A Strategic Assessment” (European Cybercrime Centre, 2013), https://www.europol.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/efc_strategic_assessment__public_version.pdf.

[ix] “Manhattan U.S. Attorney Announces Charges Against Liberty Reserve, One of World’s Largest Digital Currency Companies, And Seven of its Principals and Employees for Allegedly Running a $6 Billion Money Laundering Scheme,” Press Release (US Department of Justice, May 28, 2013), https://www.justice.gov/usao-sdny/pr/manhattan-us-attorney-announces-charges-against-liberty-reserve-one-world-s-largest

[x] “Towards Zero: An Initiative to Reduce the Availability of Child Sexual Abuse Material on the Internet” (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2023), https://www.unodc.org/pdf/criminal_justice/endVAC/EGM/EGM_CSAM_Removal_Background_Paper.pdf.

[xi] Alison Jimenez, “Crypto Crime in Context – Breaking Down the Illicit Activity in Digital Assets: Testimony of Alison Jimenez” (House Sub-Committee on Digital Assets, Financial Technology, and Inclusion, November 15, 2023), https://docs.house.gov/meetings/BA/BA21/20231115/116579/HHRG-118-BA21-Wstate-JimenezA-20231115.pdf.

[xii] Human Trafficking Front, “How CSAM Distributors Exist on the Dark Web,” December 23, 2023, https://humantraffickingfront.org/csam-distributors-dark-web/.

[xiii] “IWF Annual Report 2021” (Internet Watch Foundation, 2021), https://annualreport2021.iwf.org.uk/.

[xiv] “Websites offering cryptocurrency payments for child sexual abuse images ‘doubling every year’” (Internet Watch Foundation, November 1, 2022), https://www.iwf.org.uk/news-media/news/websites-offering-cryptocurrency-payment-for-child-sexual-abuse-images-doubling-every-year/

[xv] “Subject Matter Expert Working Group Reports” (Department of Justice, 2023), https://www.justice.gov/d9/2023-06/sme_wg_reports_combined_2.pdf.

[xvi] Samuel Lovett, “The Rise of Live-Streamed Child Abuse – and Britain’s Role in It,” The Telegraph, March 11, 2024, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/global-health/terror-and-security/live-streamed-child-abuse-philippines-surges-britain-demand/.

[xvii] “Cryptocurrencies – Tracing the Evolution of Criminal Finances,” Europol Spotlight (Europol, 2021), https://www.europol.europa.eu/cms/sites/default/files/documents/Europol Spotlight – Cryptocurrencies – Tracing the evolution of criminal finances.pdf.

[xviii] “Towards Zero: An Initiative to Reduce the Availability of Child Sexual Abuse Material on the Internet” (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2023), https://www.unodc.org/pdf/criminal_justice/endVAC/EGM/EGM_CSAM_Removal_Background_Paper.pdf.

[xix] “The Annual Report 2022: #BehindTheScreens” (Internet Watch Foundation, 2022), https://annualreport2022.iwf.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/IWF-Annual-Report-2022_FINAL.pdf

[xx] “Report of the Attorney General’s Cyber Digital Task Force” (US Department of Justice, 2020), https://www.justice.gov/cryptoreport.

[xxi] “South Korean National and Hundreds of Others Charged Worldwide in the Takedown of the Largest Darknet Child Pornography Website, Which Was Funded by Bitcoin,” Press Release (US Department of Justice, October 16, 2019), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/south-korean-national-and-hundreds-others-charged-worldwide-takedown-largest-darknet-child.

[xxii] Julia Hollingsworth, “How Police Busted a Graphic Child Exploitation Website,” CNN, October 20, 2019, https://www.cnn.com/2019/10/19/asia/south-korea-child-exploitation-international-police-intl-hnk/index.html.

[xxiii] Angus Berwick and Tom Wilson, “Crypto Exchanges Enabled Online Child Sex-Abuse Profiteer,” Reuters, November 23, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/fintech-crypto-abuse/.

[xxiv] “Dark Web Child Abuse: Administrator of DarkScandals Arrested in the Netherlands,” Press Release (Europol, March 12, 2020), https://www.europol.europa.eu/media-press/newsroom/news/dark-web-child-abuse-administrator-of-darkscandals-arrested-in-netherlands.

[xxv] “FinCEN Calls Attention to Online Child Sexual Exploitation Crimes,” FinCEN Notice (US Treasury Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), September 16, 2021), https://www.fincen.gov/sites/default/files/shared/FinCEN%20OCSE%20Notice%20508C.pdf.

[xxvi] “FinCEN Sees Increase in BSA Reporting Involving the Use of Convertible Virtual Currency for Online Child Sexual Exploitation and Human Trafficking,” Press Release (Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, February 13, 2024), https://www.fincen.gov/news/news-releases/fincen-sees-increase-bsa-reporting-involving-use-convertible-virtual-currency.

[xxvii] “Use of Convertible Virtual Currency for Suspected Online Child Sexual Exploitation and Human Trafficking: Threat Pattern & Trend Information, January 2020 to December 2021,” Financial Trend Analysis (Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, February 2024), https://www.fincen.gov/sites/default/files/shared/FTA_Human_Trafficking_FINAL508.pdf.

[xxviii] Ibid.

[xxix] “The First Crypto War? Assessing the Illicit Blockchain Ecosystem One Year Into Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine,” TRM Insights (TRM, February 23, 2023), https://www.trmlabs.com/post/the-first-crypto-war-assessing-the-illicit-blockchain-ecosystem-one-year-into-russia-ukraine-war.

[xxx] Chainalysis Team, “Making Cryptocurrency Part of the Solution to Human Trafficking,” Chainalysis (blog), April 21, 2020, https://www.chainalysis.com/blog/cryptocurrency-human-trafficking-2020/.

[xxxi] “How Financial Professionals Like You Can Help Combat Child Sexual Exploitation,” Association of Certified Anti-Money Laundering Specialists (conference panel), April 9, 2024.

[xxxii] Alison Jimenez, “Why Some Criminals Love Crypto,” Dynamic Securities Analytics, Inc. (blog), January 3, 2024, https://securitiesanalytics.com/why-some-criminals-love-crypto/.

[xxxiii] “In the Matter of Binance Holdings Limited, Binance (Services) Holdings Limited, Binance Holdings (IE) Limited, d/b/a Binance and Binance.Com: Consent Order Imposing Civil Money Penalty” (US Treasury Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), November 21, 2023), https://www.fincen.gov/sites/default/files/enforcement_action/2023-11-21/FinCEN_Consent_Order_2023-04_FINAL508.pdf.

[xxxiv] “In the Matter of Coinbase, Inc.: Consent Order” (New York State Department of Financial Services, January 4, 2023), https://www.dfs.ny.gov/system/files/documents/2023/01/ea20230104_coinbase.pdf.

[xxxv] “In the Matter of Bittrix, Inc.: Consent Order Imposing Civil Money Penalty” (US Treasury Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), April 4, 2023), https://www.fincen.gov/sites/default/files/enforcement_action/2023-04-04/Bittrex_Consent_Order_10.11.2022.pdf.

[xxxvi] “The National Strategy for Child Exploitation Prevention and Interdiction: A Report to Congress” (U.S. Department of Justice, 2016), https://www.justice.gov/d9/pages/attachments/2016/04/19/2016_natl_strategy_rpt_-_online_version_updated_final_08_16_2016.pdf.

[xxxvii] “Sextortion: It’s More Common than You Think,” U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, August 22, 2023, https://www.ice.gov/features/sextortion.

[xxxviii] Alex Hern, “Child Sexual Abuse: Self-Generated Imagery Found in Over 90% of Removed Webpages,” The Guardian, January 17, 2024, https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2024/jan/17/child-sexual-abuse-self-generated-data-internet-watch-foundation-end-to-end-encryption.

[xxxix] “Trends Identified in CyberTipline Sextortion Reports” (National Center For Missing and Exploited Children, 2016), https://www.missingkids.org/content/dam/missingkids/pdfs/ncmec-analysis/sextortionfactsheet.pdf

[xl] Rikki Schlott, “Parents Reveal Teen Sons Committed Suicide after ‘Sextortion,’” New York Post, August 30, 2023, https://nypost.com/2023/08/30/parents-reveal-teen-sons-committed-suicide-after-sextortion/.

[xli] “For-Profit Companies Charging Sextortion Victims for Assistance and Using Deceptive Tactics to Elicit Payments,” Public Service Announcement (Federal Bureau of Investigation, April 7, 2023), https://www.ic3.gov/Media/Y2023/PSA230407.

[xlii] Olivia Carville, “Scammers are targeting teenage boys on social media – and driving some to commit suicide,” April 15, 2024, https://www.bloomberg.com/features/2024-sextortion-teen-suicides/ .

[xliii] Paul Raffile et al., “A Digital Pandemic: Uncovering the Role of ‘Yahoo Boys’ in the Surge of Social Media-Enabled Financial Sextortion Targeting Minors,” Threat Intelligence Report (Network Contagion Research Institute, January 2024), https://networkcontagion.us/reports/yahoo-boys/.

[xliv] Greg Iacurci, “FBI: ‘Financial Sextortion’ of Teens Is a ‘Rapidly Escalating Threat.’ How Parents Can Protect Their Kids,” CNBC, February 1, 2024, https://www.cnbc.com/2024/02/01/fbi-financial-sextortion-of-kids-is-escalating-what-parents-can-do.html.; USA v. Shanu, No. 1:23-cr-00296 (Idaho District Court 2023), https://www.pacermonitor.com/public/case/51399976/USA_v_Shanu. An indictment is merely an allegation. All defendants are presumed innocent until proven guilty beyond a reasonable doubt in a court of law.

Want more Cryptocurrency Insights?

Why Some Criminals Love Cryptocurrency

Cryptocurrency Suspicious Activity Report Enforcement Actions

Cryptocurrency Traceability: Unraveling Underlying Assumptions