Part 4 of this five-part series examines methods of sextortion international money laundering.

Catch up below on earlier articles analyzing the financial mechanisms of financially motivated sextortion of minors.

Part 1: Introduction to Financially Motivated Sextortion of Minors

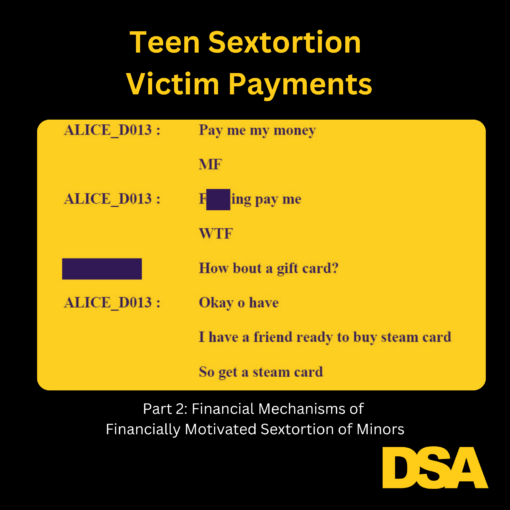

Part 2: Teen Sextortion Victim Payments

Part 3: Consolidating and Laundering Sextortion Proceeds

International Money Laundering Challenges

Perpetrators of financially motivated sextortion of minors seek financial gain. The leaders of the Transnational Criminal Organizations running sextortion schemes are often located overseas. Therefore, the sextortion ransom proceeds paid by U.S. teen victims must be moved across international borders to end up in the pockets of the TCOs.

Remitting illicit proceeds across borders poses unique challenges to money launders for several reasons. First, only certain financial products can transfer value across borders and some of those products have dollar amount limits. Second, differences in the sending and receiving countries’ financial systems may impede cross-border flows of a given product. Finally, financial institutions may view international transactions as higher risk and provide heightened scrutiny, increasing the odds that the transfer will fail.

Three case studies examined in this series OGOSHI, SHANU, and AINA were based out of Nigeria, while KONE was based out of Cote d’Ivoire (Ivory Coast). As we will see, the methods used to remit proceeds to Nigeria versus Cote d’Ivoire were strikingly different.

Nigeria: Sextortion International Money Laundering

Cryptocurrency & Financially Motivated Sextortion

All three Nigerian financially motivated sextortion schemes used cryptocurrency as the sole method to remit illicit proceeds to perpetrators in Nigeria from the United States.

As I discuss in “Why Some Criminals Love Cryptocurrency,” being able to move value far, across borders, via cryptocurrency is highly valued by some criminals. Those criminals, however, need to be able to convert the crypto back into local currency.

Importantly, Nigeria is ranked high in global ‘adoption’ of cryptocurrency. Nigerians have access to local, international, and peer-to-peer crypto platforms. Thereby, sextortion proceeds generated in the U.S. can be converted to crypto and ultimately sold for local Nigerian currency, completing the cycle.

Case Studies

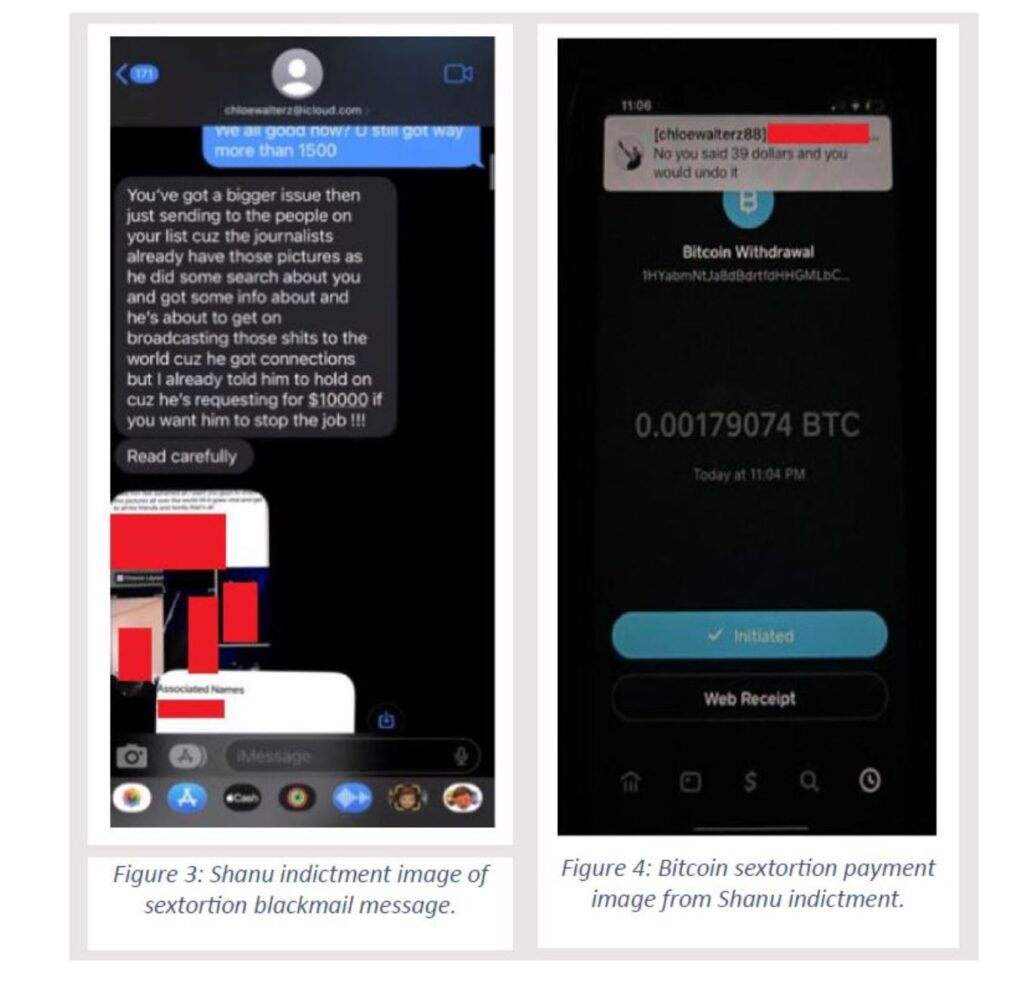

SHANU

A victim in the SHANU scheme made direct cryptocurrency — specifically bitcoin– payments via Cash App and a Bitcoin ATM to a wallet address “1HYab” provided by the perpetrators. This same victim was also coerced into receiving payments from other victims and “sending them on to the conspirators” at the 1HYab address. The conspirators provided the victim with a second wallet address “bc1qh” for deposits into that account as well.

Per the indictment:

Investigators determined the bc1qh address to be an unhosted wallet that was used to make transfers to the 1HYab address. In turn, the 1HYab address was determined to be an address hosted by Binance.

In response to a legal request, Binance provided KYC information for the individual associated with address 1HYab including phone number, IP address, devices accessing the account, email address, images of the individual’s passport and selfie.

The information provided by Binance indicated that the 1HYab address had received and delivered over $2.5 million dollars over a three-year period and targeted an estimated 6,000 victims. Investigators surmised that 1HYab was used:

“as a funnel account to receive funds from multiple sources, many of which have been identified from victims from various fraud schemes, including sextortion and romance scams.”

How did the perpetrators convert the bitcoin into local currency?

Investigators determined that SHANU typically sold the funds deposited into the 1HYab address to other Binance users in exchange for Nigerian currency (Naira) which he then deposited into Nigerian bank accounts held in his name.

AINA

As discussed in Part 2- Victim Payments, an undercover FBI employee contacted an account used to extort a victim, J.S., (who had committed suicide unbeknownst to the conspirators) and was instructed to make a payment to a specific cryptocurrency address.

The FBI tracked the bitcoin sextortion ransom payment from the address provided by the conspirator to an address associated with Binance. Binance provided records associated with the account (ABIODUN) in response to a subpoena. Per the indictment, ABIODUN confessed to receiving bitcoin, and then paying AINA.

Elsewhere in the indictment, ABIODUN was shown to have used a Nigerian payment processing service to transfer funds to AINA. The indictment does not detail how the bitcoin sextortion payments were converted to local currency (Naira) in Nigeria. AINA admitted to operating phone numbers associated with the accounts used to extort J.S.

Investigators also subpoenaed WhatsApp and Google. A review of emails identified additional cryptocurrency accounts in the name of another individual (ADEWALE) at Blockchain.com and Paxful.

The indictment states:

“according to ADEWALE, he now moves money for people. ADEWALE stated that he calls himself a ‘Picker’ or a middleman for ‘Yahoo’ money transactions.”

And

“ADEWALE admitted, that in approximately December 2022 and January 2023, ADEWALE was sending and receiving money on ABIODUN’s behalf. ADEWALE stated that he would typically receive a payment, retain a portion of that payment, and then transfer the balance to ABIODUN.”

OGOSHI

The OGOSHI case had two separate but related indictments: the first against three Nigerians running the extortion, and the second, against five U.S.-based individuals alleged to have laundered victim sextortion payments for profit.

The indictment against the money launders read:

Object of the Conspiracy

The object of the conspiracy was to enrich participants by laundering fraud proceeds.

Manner and Means

- Victims of the sextortion scheme were instructed to send money to Defendants’ financial accounts through various cash applications, like Apple Pay, Cash App, Zelle, and others.

- Defendants kept a portion of the victims’ funds, typically 20%, and they converted the rest into bitcoin.

- Defendants then sent the bitcoin to an unindicted Nigerian co-conspirator, who they referred to as the Plug. The Plug kept a portion of the bitcoin funds, and sent the remainder to Samuel Ogoshi, Samson Ogoshi, Ezekiel Robert, and other sextortionists.

- The laundered transactions include but are not limited to the following: on or about March 25, 2022, Victim 1 sent $300 via Apple Pay to Green. Green transferred a portion of those Apple Pay funds into CashApp funds. Using those CashApp funds, Green purchased bitcoin, which he sent to the Plug. The Plug kept a portion of the funds and sent the remainder to the sextortionists.

The five defendants were charged with wire fraud and conspiracy to commit money laundering offenses.

Summary: Nigeria International Money Laundering through Crypto

Nigeria-based sextortion gangs used two methods to remit proceeds through cryptocurrency. In some instances, victims purchased cryptocurrency through US-based apps or bitcoin ATMs and transferred the bitcoin to addresses provided by the sextortionists. In other cases, conspirators allegedly pooled victim ransoms made via various payment apps and used those funds to purchase cryptocurrency.

Cote d’Ivoire: Sextortion International Money Laundering

Cote d’Ivoire (CI) does not have a robust cryptocurrency marketplace, unlike Nigeria. The lack of a way to “cash out” crypto to local currency seems to thwart Cote d’Ivoire sextortion groups from using cryptocurrency in international money laundering. Instead, CI sextortion groups use a variety of methods to transfer value across borders.

All the cross-border methods described below relate to the alleged KONE scheme. The superseding indictment brought charges against a network of five U.S.-based money mules and one CI-based sextortionist. The KONE scheme allegedly received at least $1.9 million dollars in sextortion payments and targeted more than 2,000 victims. See Part 3 – Consolidating and Laundering Funds, to review how the money mules operated within the U.S.

Exporting Goods

Conspirators allegedly purchased goods by obtaining the identifiers of stored value cards (gift cards) provided by victims as sextortion payments. The purchases included luxury clothing, computers, and cell phones in the United States. Conspirators then re-shipped the goods to Cote d’Ivoire where the items were sold.

Traditional Money Transmitter

The mules delivered “cash in-person to a money transfer location like Western Union, MoneyGram, Sendwave, or Orange” and transferred the funds to individuals located in CI.

The indictment states that the CI-based conspirator instructed the US-based mule to use his mother’s name as the recipient of an Orange monetary transfer and describe the reason for the payment as “family support/living expenses.”

Hawala / Informal Money Transfer

The indictment states that the money mules transferred value overseas by:

“delivering cash in-person to a New York-based money transmitter (‘Individual A’), who arranged for funds to be converted to local currency and paid out in Cote d’Ivoire”.

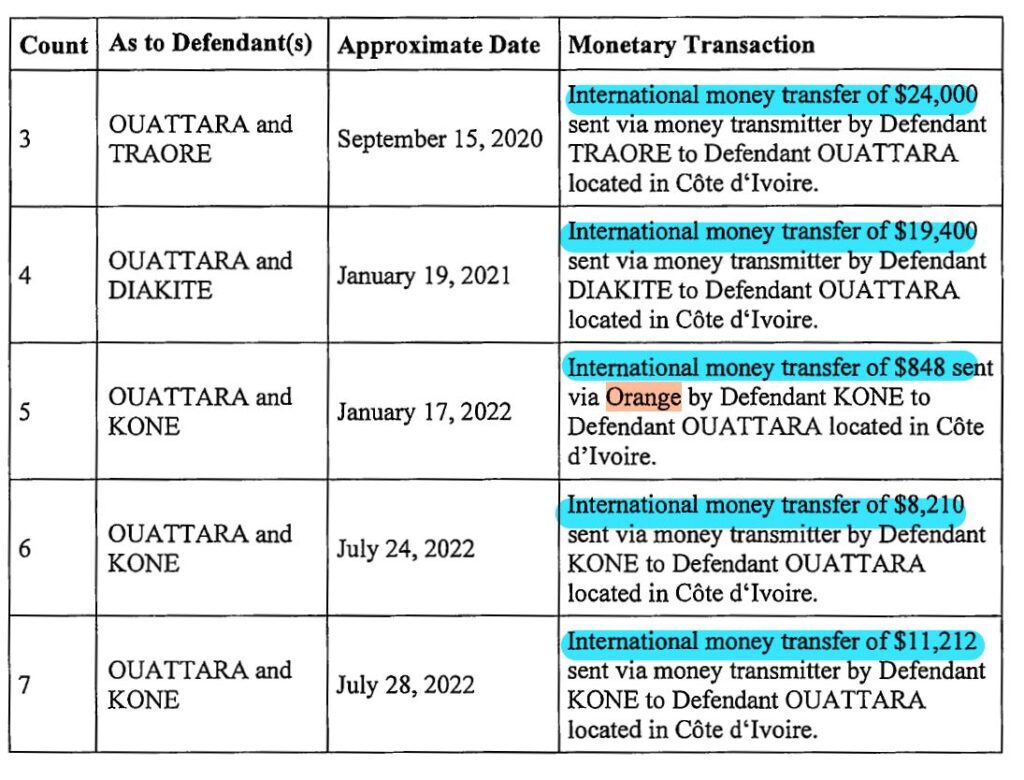

The indictment lists four separate money transfers through Individual A ranging from $8,210 to $24,000.

Comparison: Nigeria vs Cote d’Ivoire Sextortion International Money Laundering

The upsides of using cryptocurrency to internationally launder illicit proceeds is illuminated by the contrasting methods used by Nigerian versus Cote d’Ivoire sextortion gangs.

Consider the amount of time, effort, expense, and potential slippage required for the perpetrators in Cote D’Ivoire to receive illicit proceeds by converting gift cards into goods. A U.S. conspirator would need to first buy the goods (for example laptops), then pay to re-ship the laptops to Cote d’Ivoire. Once the laptops arrive in Cote d’Ivoire, the folks on that end would need to find buyers for the laptops, which may be sold for less than the purchase plus transport costs. All said, it might take weeks or months for conspirators in Cote d’Ivoire to finally receive illicit proceeds in local currency.

On the other hand, bitcoin sextortion proceeds can be remitted to conspirators in Nigeria in a matter of minutes. The conversion of bitcoin to Naira may take a bit longer as a match between sellers and buyers is required. However, media reports suggest that some Nigerians have sought to protect their savings from high inflation rates by converting Naira into cryptocurrency. Therefore, the local demand for cryptocurrency to hedge against inflation can be met by sextortionists and other fraudsters seeking to cash out bitcoin to local currency.

Surprisingly, despite the seemingly different levels of effort, both methods paid 20% to complicit money mules / professional moneys for their services.

An indictment is merely an allegation. Individuals are presumed innocent until proven guilty in a court of law. Two individuals named in the OGOSHI matter pleaded guilty and were sentenced to seventeen years in prison. One individual associated with the KONE matter has pleaded guilty to one count of conspiracy to engage in money laundering.

Dynamic Securities Analytics, Inc. provides litigation consulting to help clients successfully navigate disputes involving securities, cryptocurrency, and money laundering.